Euripides’s last great tragedy, the Bacchae, shows a new divinity proclaimed in Greece from Asia, Dionysus, reputed to be son of Zeus. The ruler of Thebes, Pentheus, wants nothing to do with this dubious god of wine, dance, and ecstasy. (The festival of Dionysus provided Greek playwrights the occasion to compete in tragedy and comedy, which as performances are ritualized ecstasies. We shall try to experience some of this ourselves.) Euripides’ play raises these two questions: what is the proper response to divine incursions, pretended or real, that upset familiar relations of men and women, young and old, citizen and stranger? And what is the proper divine response to human blasphemy?

Euripides’s last great tragedy, the Bacchae, shows a new divinity proclaimed in Greece from Asia, Dionysus, reputed to be son of Zeus. The ruler of Thebes, Pentheus, wants nothing to do with this dubious god of wine, dance, and ecstasy. (The festival of Dionysus provided Greek playwrights the occasion to compete in tragedy and comedy, which as performances are ritualized ecstasies. We shall try to experience some of this ourselves.) Euripides’ play raises these two questions: what is the proper response to divine incursions, pretended or real, that upset familiar relations of men and women, young and old, citizen and stranger? And what is the proper divine response to human blasphemy?

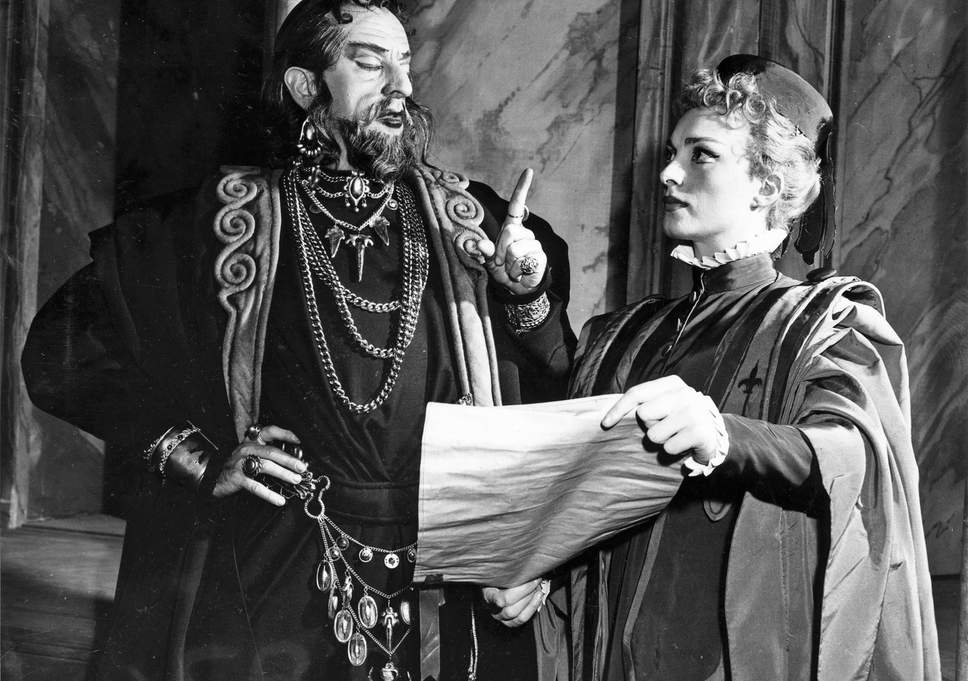

Shakespeare’s controversial The Merchant of Venice (technically classified as a comedy) pits old Shylock, a Jewish money-lender, against a Christian merchant, Antonio, over questions of love (several kinds), family, law, justice, and underlying all of these: how to interpret the words we live by. Shylock has the opportunity to become a tragic hero in vindication of law over charity, but he chooses to save his life by converting to Christianity rather than killing his great enemy. Shakespeare tears at our sympathies as we watch the action, and makes us wonder how to respond to a call for mercy that upsets an ancient grudge, based on different conceptions of truth and ethics held by our common humanity.