The Hasidic group known both as Lubavitch, after a town in Russia, and as Chabad, an acronym for the three elements of human and divine intelligence, Chochma (wisdom), Bina (understanding), and Da’at (knowledge), is not just the most successful contemporary Hasidic sect. It might be the most successful Jewish religious movement of the second half of the twentieth century.

While mainstream Orthodox Judaism has seen extraordinary growth through the ba’al teshuvah movement of “returners” to religious observance, the foundations were laid by Chabad. And while Orthodox Jews often express disdain for Chabad and its fervent shluchim (emissaries), they also rely on them for prayer services, Torah study, and kosher accommodations in out-of-the-way places from Jackson,Wyoming to Bangkok, Thailand, not to speak of college campuses around the world.

The Conservative movement historically caters to moderate suburban traditionalists. But many suburbanites now find themselves more comfortable at Chabad’s user-friendly services. Once the source of a distinctive middle-class Jewish nightmare—that one’s child might come home with tzitzis, a fedora, and extraordinary dietary demands (an “invasion of the Chabody snatchers,” as a joke of my childhood had it)—Lubavitch is now a familiar part of the suburban landscape.

For decades, the Reform movement has defined its mission as tikkun olam, “repair of the world,” understood not as metaphysical doctrine but as social justice. And yet it is the unabashedly metaphysical Chabad that opens drug rehabilitation centers, establishes programs for children with special needs, and caters to Jewish immigrants, to name just three of a seemingly endless list of charitable activities.

Finally, the charismatic founders of the groovy Judaism that arose in the 1960s, from the liberal Renewal movement to Neo-Hasidic Orthodoxy, were Rabbis Shlomo Carlebach and Zalman Schachter-Shalomi. Both began their careers as shluchim of the sixth Lubavitcher Rebbe in the late 1940s and continued under his successor before branching out on their own. Although neither remained within Chabad, both retained its can-do entrepreneurial flair, as well as a spark, as it were, of the Rebbe’s charisma.

Each of these points needs qualification, but each could also be amplified. Despite its tiny numbers—at a generous guess, Lubavitchers have never comprised more than one percent of the total Jewish population—the Chabad-Lubavitch movement has transformed the Jewish world. It also has enviable brand recognition. This extends from the distinctive black suits, untrimmed beards, and genuine warmth of Chabad shluchim to renegade but still recognizably Chabad-ish figures like the reggae pop star Matisyahu and religious pundit Shmuley Boteach. But, most of all, Chabad is recognized in the saintly and ubiquitous visage of the late seventh Lubavitcher Rebbe, Menachem Mendel Schneerson, which has become, almost literally, a kind of icon.

By almost any conceivable standard, then, Chabad-Lubavitch has been an extraordinary success, except by the one standard that it has set itself: It has not ushered in the Messiah. It has, however, been the source of the greatest surge of Jewish messianic fervor (“We want Moshiach now and we don’t want to wait!”) since the career of Shabbtai Tzvi, the failed messiah of the seventeenth century. In fact, there are an indeterminate number of messianist Lubavitchers (meshikhistn) who continue to believe that the Rebbe did not truly die in 1994, and will return to complete his messianic mission. This is repudiated by the central organization of Chabad, though not as unequivocally as some critics would like. In any case, a successor to Schneerson seems inconceivable even to such moderates.

This raises a large question. It is often said of Chabad that the success of its institution-building and good works are unfortunately marred by its ardent messianism during the Rebbe’s life and especially after his death. But what if this messianism was the motivating force that actually made their success possible? If so, we would be presented with a kind of paradox: the belief that underlies the Lubavitchers’ success may yet undo them entirely.

None of this would have been likely or even possible had the movement not been headed, since 1951, by the subject of sociologists Samuel Heilman and Menachem Friedman’s ambitious and already controversial new biography, The Rebbe: The Life and Afterlife of Menachem Mendel Schneerson.

Menachem Mendel Schneerson was born in 1902 in Ukraine to a distinguished Lubavitcher family. Heilman and Friedman sketch his early life, but their most striking biographical claims come in the chapters on his young adult years. It used to be said that in the 1920s and ‘30s, Schneerson had received degrees from the University of Berlin and the Sorbonne. Actually, Friedman and Heilman show that when Schneerson left Russia for Germany he did not have a diploma and so was unable to seek regular admission to a university. Instead, he applied to audit courses at the neo-Orthodox Hildesheimer Rabbinical Seminary, which in turn allowed him to audit courses at Friedrich Wilhelm University. Later, in Paris, he received an engineering degree from the École Spéciale des Travaux Publics du Bâtiment et de l’Industrie, and went on to study mathematics at the Sorbonne before being forced to flee the occupying Nazis.

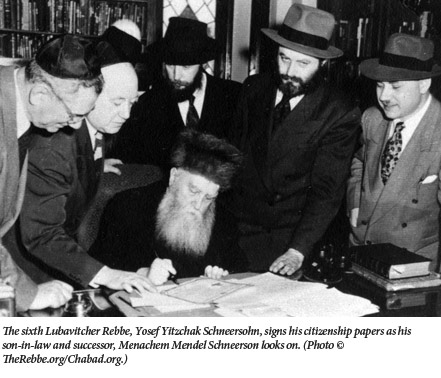

It was while auditing courses in philosophy and mathematics in Berlin that Schneerson married Moussia (or Chaya Mushka), the daughter of Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, the sixth Lubavitcher Rebbe (the bride and groom were distantly related). Here Heilman and Friedman strive mightily to show that, far from being destined to succeed his father-in-law as Rebbe, Menachem Mendel and his new wife were trying out a less Hasidic, more cosmopolitan lifestyle. They write that “visitors of the few Hasidic congregations” in Berlin never saw Schneerson in attendance, and that he and Moussia liked to go out on the town on Monday nights. They also scant his Jewish study, and, almost as provocatively, strongly suggest that he trimmed his beard. In these chapters, Schneerson is described as leading a “double life.”

This is interesting, and may be true in some sense, but it would be more persuasive if Heilman and Friedman really had the goods. When one checks the endnote for who didn’t see Menachem Mendel Schneerson in shul, the only name turns out to be that of Yosef Burg. In the 1980s, the prominent Israeli politician told Friedman that he did not remember seeing Schneerson—a half century after the fact. What about those nights out in Weimar-era Berlin? They are mentioned on the authority of the “recollections of Barry Gourary,” a nephew who was five years old, lived in Latvia at the time, and later became bitterly estranged from his aunt and uncle.

The question of Schneerson’s rabbinic learning, his beard, and the couple’s years in Berlin and Paris have been the subject of a furious dispute between Samuel Heilman and Chaim Rapoport on a popular Orthodox blog site, Seforim. Although somewhat self-righteous and bombastic, Rapoport has gotten the better of the exchange. Even on Heilman and Friedman’s account, for instance, it emerges that during the period when Schneerson is supposed to have avoided Hasidic shtiblekh, he was piously fasting every day until the afternoon. Heilman and Friedman hypothesize that this was because he and Moussia were childless, but as Rapoport points out, he began the practice immediately after marriage. The fact that the Schneersons never had children is of extraordinary biographical and historical importance (if they had, the possibility of an eighth Lubavitcher Rebbe might have seemed more thinkable), but Schneerson would have had to be a prophet to begin worrying about this in 1929.

More importantly, Rapoport shows that remarks such as “a look through [Schneerson’s] diary . . . reveals that he had been collecting and absorbing the myriad customs of Lubavitcher practice for years” seriously understate the extent of Schneerson’s learning and piety. Schneerson’s posthumously published diary, Reshimot, along with his learned correspondence with his father and father-in-law, present a picture of someone thoroughly engaged in the intellectual worlds of rabbinic thought, Kabbalah, and Hasidism. Occasionally, one even finds him working to integrate all of this with his scientific studies. In one such entry, he links the fluidity of one’s inner experience to the traditional comparison of Torah with water, as well as to Pascal’s law of hydrostatic pressure.

This is hardly to deny that Schneerson contemplated leading a life devoted to engineering and science rather than religious leadership; the years of difficult schooling are inexplicable otherwise. But it is a failure of biographical research and imagination on Heilman and Friedman’s part not to have critically culled Schneerson’s correspondence and journals to give a sense of his inner life in all of its fluidity. He was an aspiring engineer and a kabbalist, but since Heilman and Friedman take an extremely selective approach to the letters and journals of this period of his life, they fail to portray the second half of the equation. In part, this is because the sources were edited within a Chabad movement zealously dedicated to the memory of its Rebbe, but it plainly also has to do with the difficulty of the material.

Their circumstantial approach to biography reaches its height, or depth, in Heilman and Friedman’s account of the Schneersons’ years in Paris. The couple chose to live in the fourteenth arrondissement, far from synagogues but just moments from the café Le Select where “one could find the most outrageous bohemian behavior” and within hailing distance of some of Sartre and Beauvoir’s favorite haunts. “Could the Schneersons have remained completely ignorant of this life around them?” Heilman and Friedman ask. Based on the evidence presented, my guess would be mostly yes. (One would like to know more about Moussia, who read Russian literature and attended the ballet, but she remains a cipher throughout the book, as does the Schneersons’ marital relationship).

As for whether Schneerson cut his beard as a young man, I remain agnostic, if not apathetic. A photograph from the period shows a dapper Schneerson in a brown suit, light-colored hat, and short beard, standing on a bridge and looking out at the water. But Lubavitchers sometimes comb their beards under and pin them to achieve a neat look. Hedging, Heilman and Friedman describe the beard as “trim-looking,” but they clearly think scissors were involved and that his father-in-law was furious. Yet in pictures taken two decades later, after he had already become the Rebbe, Schneerson still looks well-groomed. In one, he stares back at the camera, his eyes framed by a sharp black hat and a trim black beard, looking a little like a rabbinic Paul Muni.

Lives of saints have a sense of fatedness or inevitability that Heilman and Friedman are certainly right to avoid. Menachem Mendel Schneerson was not predestined to become the seventh Rebbe, let alone the Messiah.

There was, in fact, significant opposition to his succeeding his father-in-law. In the first place there was his mother-in-law. Nechama Dina Schneersohn favored her other son-in-law, Rabbi Shmaryahu Gourary (the above-mentioned Barry’s father), who had been at her husband’s side while Schneerson was studying in Berlin and Paris. Schneerson’s ascension was not immediate, and his eventual victory left a deeply divided family. Symbolically, his mother-in-law refused to allow him to wear her husband’s shtrayml, the fur hat worn on Shabbat, Holy Days, and important occasions. Heilman and Friedman describe Schneerson’s pragmatic response with a rare sense of admiration:

Rabbi Menachem Mendel handled this as he

handled other challenges, with creativity. He

simply removed the use of shtraymls from

Chabad rabbinic practice and was forever

after seen only in his trademark black snap

brim fedora.

Schneerson was clearly an inspired tactician and executive, with a genius for public relations. Again and again, Heilman and Friedman show, he was able to inspire and empower his followers to strike out in the world and spread the message of the need to perform more ritual commandments and acts of lovingkindness. But they also see a pattern. Near the end of his great twelfth-century code of Jewish law, the Mishneh Torah, Maimonides lays out the criteria for the true Messiah:

If a king arises from the House of David who delves deeply into the study of the Torah … if he compels all Israel to walk in [its ways] … and fights the wars of God, he is presumed to be the Messiah. If he succeeds and builds the Holy Temple on its site and gathers the scattered remnants of Israel, then he is certainly the Messiah.

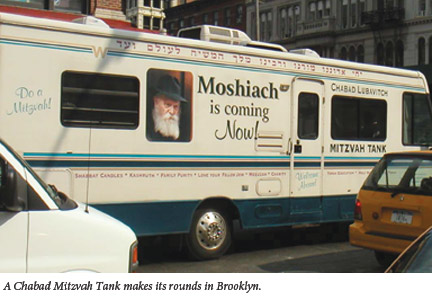

If one identifies the “kingship” of Lubavitch with that of the House of David, then the Rebbe’s missionary work through his many public campaigns—to encourage the lighting of Shabbat candles, the wearing of tefillin, and so on—can be seen as steps toward fulfilling the second criterion. And what of “the wars of God”? The Chabad youth group Tzivos Hashem, or the “Army of God,” was established under the leadership of a Rebbe who also dispatched “mitzvah tanks” emblazoned with inspirational slogans. Perhaps more speculatively, Heilman and Friedman also argue that the Rebbe competed with the State of Israel by taking spiritual credit for its military victories. In short, the overarching goal of Chabad’s activities was to make the Rebbe the presumptive Messiah and “force the end” of history, to use a classic (and disparaging) Rabbinic phrase.

Certainly, this is how many if not most of his Hasidim seem to have understood these activities at the time. Although he often rebuked those who publicly urged him to declare his Messianic kingship, what they took him to mean was “not yet.” They were probably right. It is a Chabad doctrine that there is a potential savior in every generation, and it seems unlikely that Schneerson thought that it was somebody else. Friedman and Heilman say that he hinted at this when he used the Hebrew word mamash. The word means really, or actually, but it can also be taken as an acronym for the name Menachem Mendel Schneerson. Thus, on the occasion of being honored by President Ronald Reagan he said that the “Messiah is coming soon, mamash,” and he is reported to have later repeated the assurance, adding “with all its interpretations.”

The parsing of such proclamations may sound trivial, but the radical seriousness with which

Schneerson and his followers took their spiritual task should not be underestimated. He really does seem to have felt responsible for all Jews and to have conveyed a sense of this deep caring to virtually each of the thousands who sought an individual audience, or “yechidus,” with him. His followers took this same sense of care to the streets and around the world, and continue to do so.

Schneerson’s charisma was palpable even to non-followers. Norman Mailer, a connoisseur of charisma if not of theology, felt it when he and Norman Podhoretz visited Chabad headquarters at 770 Eastern Parkway for kol nidrei in 1962. The willingness of non-Hasidim to tell miraculous tales of the Rebbe also suggests an extraordinary personality that is sadly not on display in The Rebbe. Even if he was not the Messiah, the Rebbe may have been the most influential Hasidic leader since the founder of the movement, Israel Ba’al Shem Tov. Heilman and Friedman’s biography simply doesn’t show us how Schneerson became that person.

The Rebbe does show that the messianism, which burst into public awareness in the 1970s and ’80s, was present from the outset of Schneerson’s leadership, and had its roots in his father-in-law’s understanding of Hasidism.

In 1751, the Ba’al Shem Tov described a vision in which he ascended to heaven:

I entered the palace of the Messiah, where he studies with all the Rabbinic sages and the righteous . . . I asked, “when are you coming, sir?” He answered me: ” . . . [not] until your teaching has become renowned and revealed throughout the whole world . . . I was bewildered at this [and] I had great anguish because of the length of time when it would be possible for this to occur.

Gershom Scholem, the great historian of Jewish mysticism, saw this postponement as evidence that Hasidism was, in part, an attempt to neutralize the kabbalistic messianism of Shabbtai Tzvi and his followers while retaining its popular dynamism. His interpretation has been the subject of much scholarly controversy but it fits the Tanya, the first work of Chabad Hasidism, by its founder Schneur Zalman of Liadi. The “Alter Rebbe,” as he is known within Chabad, describes messianic redemption as the final illumination of the revelation begun at Sinai, but it does not sound imminent.

However, by Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn’s reign there had been seven generations of Hasidic Rebbes who had followed the Ba’al Shem Tov, and six generations of Lubavitcher Rebbes. As early as 1926, Yosef Yitzchak emphasized the importance of a midrashic statement that “all sevens are dear to God.” In the 1940s, after experiencing the depredations of Communist rule and seeing some of his family and much of his world destroyed by the Nazis, he coined the slogan le-alter le-teshuvah, le-alter le-geulah (“repentance now, redemption now”).

Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak’s last work was entitled Basi Legani, or “I have come into my garden,” after the biblical verse, “I have come into my garden, my sister, my bride” (Song of Songs 5:1), understood as a poetic allegory of the consummation of the love between God and Israel, and also that between God and his exiled (feminine) presence, the Shekhina. It was delivered posthumously by Schneerson on the anniversary of his father-in-law’s passing, in what was to become his first address as Rebbe. Schneerson consoled his father-in-law’s Hasidim and himself by emphasizing that “the seventh is cherished.” Just as Moses and his generation had followed Abraham by seven generations, so too this generation was now the seventh Hasidic generation, whose task was to complete the process of drawing down the Shekhina. The end of the address is worth quoting at some length.

This accords with what is written concerning the Messiah: “And he shall be exalted greatly . . .”

even more than was Adam before the sin. And my revered father-in-law, the Rebbe, of blessed

memory . . . who was “anguished by our sins and ground down by our transgressions,”—just as

he saw us in our affliction, so will he speedily in our days . . . redeem the sheep of his flock

simultaneously from both the spiritual and physical exile, and uplift us to [a state where we shall

be suffused with] rays of light . . . Beyond this, the Rebbe will bind and unite us with the infinite

Essence of God . . . “Then will Moses and the Children of Israel sing . . . ‘God will reign forever and

ever,'” . . . All the above is accomplished through the passing of tzaddikim, which is even harsher than

the destruction of the Temple. Since we have already experienced all these things, everything now

depends only on us—the seventh generation. May we be privileged to see and meet with the Rebbe

here in this world, in a physical body, in this earthly domain—and he will redeem us.

Heilman and Friedman (who don’t discuss the discourse in its entirety) understand Schneerson to have been asserting from the very outset of his career that as the seventh Lubavitcher Rebbe he was destined to be the Messiah. But perhaps we ought to take him at his word here. In the sentences I have italicized, he is clearly describing his father-in-law as the Messiah who will “speedily in our days . . . redeem the sheep of his flock,” and will do so, moreover, “in a physical body, in this earthly domain.” So who was the beloved “seventh”? Schneerson may have been saying that it was his father-in-law–counting seven generations after the Ba’al Shem Tov and either placing himself as a mere member of that seventh generation under his father-in-law, or, perhaps, merging himself with his father-in-law as he does in the text. This is personally more modest but theologically bolder than the alternative, for it already sets the precedent for one of the features of present-day Lubavitcher messianism that many find so objectionable: the promise that a Messiah who has died will return a second time to complete the redemption.

Schneerson continued to elaborate on the themes of Basi Legani every year on his father-in-law’s yahrzeit. It would be interesting to see if and how the interpretation evolved, but Heilman and Friedman have little time for textual analysis of any kind. Unfortunately, this is a biography of an intellectual (Schneerson was immersed in the reading and writing of abstruse texts throughout his life) that shows little interest in his intellectual biography.

What did Schneerson think the Messianic era would look like? Elliot Wolfson’s recent book, Open Secret: Postmessianic Messianism and the Mystical Revision of Menahem Mendel Schneerson, provides an astonishing answer. Wolfson has little interest in court politics or the externals of Schneerson’s biography, but he has read his mystical writings very closely. This is not easy work. Not only did the Rebbe write an extraordinary amount (the collected Hebrew and Yiddish discourses alone comprise thirty-nine volumes), but he wrote in a rebarbative style that goes all the way back to the Tanya. Joseph Weiss once described it as “marked by long sentences, extremely condensed in character, with the main subordinate clauses often mixed up, and frequent anacoluthic constructions.” This sounds about right, as long as one adds the penchant for deliberate paradox, though there are also sudden moments of beauty.

Wolfson is a difficult writer himself but he has read the Rebbe with extraordinary sympathy and erudition. To explain the notion of primordial essence in Chabad metaphysics, he cites “Schelling’s notion of ‘absolute indifference’ of the being or essence (Wesen) that precedes all ground and is thus referred to as the ‘original ground,’ the Ungrund, literally the nonground.” On Wolfson’s reading of Schneerson, in the Messianic era all differences—those between man and woman, Jew and gentile (though Schneerson was not as consistent as he would like here) and even God and the universe—will not be erased but rather returned to something like the original nonground of Schellingian indifference.

And how will the Messiah do this? Wolfson’s interpretation is an act of hermeneutic chutzpah:

In my judgment, Schneerson was intentionally ambiguous about his own identity as

Messiah . . . Simply put, the image of a personal Messiah may have been utilized rhetorically to

liberate one from the belief in a personal Messiah . . . Schneerson’s mission from its inception is about

fostering the “true expansion of knowledge,” an alternate angle of vision . . . marked by progressively

discarding all veils in the effort to see the veil of truth unveiled in the truth of the veil.

The king, as it were, has paraded without clothes in order to show that there is no difference between being clothed and naked, or as Kafka said, “the Messiah will come only when he is no longer necessary.” One notes the postmodern resonance, but could this really be the message Menachem Mendel

Schneerson tried to teach for four decades?

In 1991, a frail 89-year-old Rebbe addressed his Hasidim poignantly:

What more can I do? I have done all I can so that the Jewish people will demand and clamor for the

redemption, for all that was done up to now was not enough, and the proof is that we are still in exile

and, more importantly, in internal exile from the worship of God. The only thing that remains for me to

do is to give over the matter to you. Do all that is in your power to achieve this thing—a sublime and

transcendent light that needs to be brought down into our world with pragmatic tools—to bring the

righteous Messiah, in fact immediately (mamash miyad).

I can see how to read this like Wolfson, but I can’t buy it. The Rebbe, I believe, meant the Messiah mamash.

Gershom Scholem once described messianism as an anarchic breeze that throws the well-ordered house of Judaism into disarray. Although the official position of the Chabad movement is that Menachem Mendel Schneerson did in fact pass away and is not (or at least not so far) the Messiah, its house remains disordered. As I write, yechi Adoneinu Morenu ve-Rabeinu Melekh ha-Moshiach le-olam va-ed is chanted at prayer services in the Rebbe’s own synagogue in the basement of Chabad headquarters. Their master and teacher and rabbi, the King Messiah will live forever. Meanwhile, the central Chabad organization, which occupies the rest of the building, seems to be nearing the end of a six-year legal battle to evict the meshikhistn. Of course the messianism extends beyond Crown Heights. My son has a handy card with the tefillat ha-derekh, the prayer for travelers on one side and a picture of the Rebbe over the word “Moshiach,” which was thrust into his hands in Jerusalem. In recent months I have seen messianist banners, bumper stickers, posters and yarmulkes in Los Angeles, Florida, and Cleveland.

To its great credit, Chabad’s worldwide operations have continued to expand in the sixteen years since the Rebbe’s death. But this fact does not quite undermine the paradox with which I began. Although many, perhaps most, within Chabad no longer live in an ecstatic anticipation of redemption, the Rebbe still seems to be the mainspring for all of their activities. It is not just that there is no eighth Lubavitcher Rebbe and is not likely to be one until the Messiah comes (after which, as Kafka might say, we might no longer need one), but that the fervent devotion to the previous Rebbe seems perilously close to crowding out other religious motivations.

Could Chabad continue to thrive if the seventh Lubavitcher Rebbe was no longer at the center of his followers’ spiritual universe? If they came to see him in a light no different than that of his predecessors—a great leader but not the Messiah, a great rebbe but not irreplacable? Can the apparently superhuman achievements of the Chabad movement continue if its Hasidim lose their superhuman inspiration? This is a problem that only Chabad can address but it is a dilemma that all Jews must confront. At stake are not only the spiritual lives of Lubavitcher Hasidim but also the camps, schools, synagogues, and programs that now serve Jews around the world.

About the Author

Abraham Socher is the Editor of the Jewish Review of Books and a professor of Jewish Studies at Oberlin College.

- Bella Brannon and Benjie Katz on Anti-Semitic Employment Discrimination at UCLA

- Ari Lamm on the Biblical Meaning of Giving Thanks

- Maury Litwack on the Jewish Vote in the 2024 Elections

- Jon Levenson on Understanding the Binding of Isaac as the Bible Understands It (Rebroadcast)

- Mark Dubowitz on the Dangers of a Lame-Duck President

- Matthew Levitt on Israel’s War with Hizballah

- Meir Soloveichik on the Meaning of the Jewish Calendar

- Elliott Abrams on Whether American Jewry Can Restore Its Sense of Peoplehood

- Assaf Orion on Israel’s War with Hizballah

- Abe Unger on America’s First Jewish Classical School

- Marc Novicoff on Why Elite Colleges Were More Likely to Protest Israel

- Liel Leibovitz on What the Protests in Israel Mean

- Gary Saul Morson on Alexander Solzhenitsyn and His Warning to America

- Adam Kirsch on Settler Colonialism

- Raphael BenLevi, Hanin Ghaddar, and Richard Goldberg on the Looming War in Lebanon

- Josh Kraushaar on the Democratic Party’s Veepstakes and American Jewry

- J.J. Schacter on the First Tisha b’Av Since October 7

- Noah Rothman on Kamala Harris’s Views of Israel and the Middle East

- Avi Weiss on the AMIA Bombing 30 Years Later (Rebroadcast)

- Melanie Phillips on the British Election and the Jews

- Mark Cohn on the Reform Movement and Intermarriage

- Jeffrey Saks on the Genius of S.Y. Agnon

- Shlomo Brody on What the Jewish Tradition Says about Going to War

- Chaim Saiman on the Roots and Basis of Jewish Law (Rebroadcast)

- Elliott Abrams on American Jewish Anti-Zionists

- Andrew Doran on Why He Thinks the Roots of Civilization Are Jewish

- Haisam Hassanein on How Egypt Sees Gaza

- Asael Abelman on the History of “Hatikvah”

- Shlomo Brody on Jewish Ethics in War

- Ruth Wisse on the Explosion of Anti-Israel Protests on Campus

- Meir Soloveichik on the Politics of the Haggadah

- Yechiel Leiter on Losing a Child to War

- Yehoshua Pfeffer on Haredi Service in the Israeli Military

- Joseph Lieberman on American Jews and the Zionist Dream (Rebroadcast)

- Seth Kaplan on How to Fix America’s Fragile Neighborhoods

- Timothy Carney on How It Became So Hard to Raise a Family in America

- Jonathan Conricus on How Israeli Aid to Gaza Works

- Vance Serchuk on Ten Years of the Russia-Ukraine War

- Yehuda Halper on Maimonides the Physician

- Cynthia Ozick on the Story of a Jew Who Becomes a Tormentor of Other Jews

- Yehuda Halper on Guiding Readers to “The Guide of the Perplexed”

- Ray Takeyh on What Iran Wants

- Yehuda Halper on Maimonides and the Human Condition

- Hillel Neuer on How the Human-Rights Industry Became Obsessed with Israel

- Yehuda Halper on Where to Begin With Maimonides

- Our Favorite Conversations of 2023

- Matti Friedman on Whether Israel Is Too Dependent on Technology

- Ghaith al-Omari on What Palestinians Really Think about Hamas, Israel, War, and Peace

- Alexandra Orbuch, Gabriel Diamond, and Zach Kessel on the Situation for Jews on American Campuses

- Roya Hakakian on Her Letter to an Anti-Zionist Idealist

- Edward Luttwak on How Israel Develops Advanced Military Technology On Its Own

- Assaf Orion on Israel’s Initial Air Campaign in Gaza

- Bruce Bechtol on How North Korean Weapons Ended Up in Gaza

- Hay Eytan Cohen Yanarocak on Whether Hamas Doomed Israeli-Turkish Relations

- Michael Doran on Israel’s Wars: 1973 and 2023

- Ethan Tucker on the Jewish Duty to Recover Hostages

- Meir Soloveichik on What Jews Believe and Say about Martyrdom

- Yascha Mounk on the Identity Trap and What It Means for Jews

- Alon Arvatz on Israel’s Cyber-Security Industry

- Daniel Rynhold on Thinking Repentance Through

- Jon Levenson on Understanding the Binding of Isaac as the Bible Understands It

- Yonatan Jakubowicz on Israel’s African Immigrants

- Mordechai Kedar on the Return of Terrorism in the West Bank

- Ran Baratz on the Roots of Israeli Angst

- Dovid Margolin on Kommunarka and the Jewish Defiance of Soviet History

- Shlomo Brody on Capital Punishment and the Jewish Tradition

- Podcast: Dara Horn on Why People Love Dead Jews (Rebroadcast)

- Podcast: Izzy Pludwinski on the Art and Beauty of Hebrew Calligraphy

- Podcast: Joshua Berman on the Traumas of the Book of Lamentations

- Podcast: Meir Soloveichik on Ten Portraits of Jewish Statesmanship

- Podcast: Nathan Diament on Whether the Post Office Can Force Employees to Work on the Sabbath

- Podcast: Yaakov Amidror on Why He’s Arguing That Israel Must Prepare for War with Iran

- Podcast: Liel Leibovitz on the Return of Paganism

- Podcast: Rick Richman on History and Devotion

- Podcast: Yuval Levin on How America’s Constitution Might Help Solve Israel’s Judicial Crisis

- Podcast: Neil Rogachevsky & Dov Zigler on the Political Philosophy of Israel’s Declaration of Independence

- Podcast: Yehoshua Pfeffer on Israel’s Social Schisms and How They Affect the Judicial Reform Debate

- Podcast: Jonathan Schachter on What Saudi Arabia’s Deal with Iran Means for Israel and America

- Podcast: Peter Berkowitz & Gadi Taub on the Deeper Causes of Israel’s Internal Conflict

- Podcast: Jordan B. Gorfinkel on His New Illustrated Book of Esther

- Podcast: Malka Simkovich on God’s Maternal Love

- Podcast: Richard Goldberg on Recent Joint Military Exercises Between America and Israel

- Podcast: Russ Roberts on the Disappointment and the Promise of Prayer

- Podcast: Joshua Berman on Traveling to Biblical Egypt

- Podcast: Elliott Abrams on American Jews and the New Israeli Government

- Podcast: Carl Gershman on What the Jewish Experience Can Offer the Uighurs of China

- Podcast: Benjamin Netanyahu on His Moments of Decision

- Podcast: Maxim D. Shrayer on the Moral Obligations and Dilemmas of Russia’s Jewish Leaders

- Podcast: Ryan Anderson on Why His Think Tank Focuses on Culture and Not Just Politics

- Podcast: Simcha Rothman on Reforming Israel’s Justice System

- Podcast: Michael Doran on Iran’s Growing Military Dominance in the Middle East

- Podcast: Scott Shay on How BDS Crept into the Investment World, and How It Was Kicked Out

- Podcast: Haviv Rettig Gur on Netanyahu, Lapid, and Another Israeli Election

- Podcast: Yoav Sorek, David Weinberg, & Jonathan Silver on What Jewish Magazines Are For

- Podcast: Tony Badran Puts Israel’s New Maritime Borders with Lebanon into Context

- Podcast: George Weigel on the Second Vatican Council and the Jews

- Podcast: Shay Khatiri on the Protests Roiling Iran

- Podcast: Meir Soloveichik on Jerusalem’s Enduring Symbols

- Podcast: Daniel Polisar on the First Zionist Congress, 125 Years Later

- Podcast: Hussein Aboubakr on the Holocaust in the Arab Moral Imagination

- Podcast: Jonathan Schanzer on Israel’s Weekend War against Islamic Jihad

- Podcast: Yair Harel on Haim Louk’s Masterful Jewish Music

- Podcast: Jacob J. Schacter on Why So Many Jewish Soldiers Are Buried Under Crosses, and What Can Be Done About It

- Podcast: Robert Nicholson on the Changing Face of Evangelical Zionism

- Podcast: Daniel Gordis & Asael Abelman on the Personality of the New Jew

- Podcast: Douglas Murray on the War on the West

- Podcast: Jeffrey Woolf on the Political and Religious Significance of the Temple Mount

- Podcast: Zohar Atkins on the Contested Idea of Equality

- Podcast: Steven Smith on Persecution and the Art of Writing

- Podcast: Jon Levenson on the Moral Force of the Book of Ruth

- Podcast: Tony Badran on How Hizballah Wins, Even When It Loses

- Podcast: John Podhoretz on Midge Decter’s Life in Ideas

- Podcast: Motti Inbari on the Yemenite Children Affair

- Podcast: Christine Emba on Rethinking Sex

- Podcast: Shany Mor on How to Understand the Recent Terror Attacks in Israel

- Podcast: Abraham Socher on His Life in Jewish Letters and the Liberal Arts

- Podcast: Ilana Horwitz on Educational Performance and Religion

- Podcast: David Friedman on What He Learned as U.S. Ambassador to Israel

- Podcast: Andy Smarick on What the Government Can and Can’t Do to Help American Families

- Podcast: Aaron MacLean on Deterrence and American Power

- Podcast: Ronna Burger on Reading Esther as a Philosopher

- Podcast: Dovid Margolin on Jewish Life in War-Torn Ukraine

- Podcast: Vance Serchuk on the History and Politics Behind Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine

- Podcast: Ruth Wisse on the Stories Jews Tell

- Podcast: Yossi Shain on the Israeli Century

- Podcast: Michael Doran on the Most Strategically Valuable Country You’ve Never Heard Of

- Podcast: Mitch Silber on Securing America’s Jewish Communities

- Podcast: Jesse Smith on Transmitting Religious Devotion

- Podcast: Matti Friedman on China’s New Haifa Port

- Podcast: Jay Greene on Anti-Semitic Leanings Among College Diversity Administrators

- Podcast: Our Favorite Broadcasts of 2021

- Podcast: Three Young Jews on Discovering Their Jewish Purposes

- Podcast: Annie Fixler on Cyber Warfare in the 21st Century

- Podcast: Victoria Coates on the Confusion in Natanz

- Podcast: Judah Ari Gross on Why Israel and Morocco Came to a New Defense Agreement

- Podcast: Michael Avi Helfand on Jewish Life and Law at the Supreme Court

- Podcast: Nicholas Eberstadt on What Declining Birthrates Mean for the Future of the West

- Podcast: Suzy Weiss on the Childless Lives of Young American Women

- Podcast: Michael Eisenberg on Economics in the Book of Genesis

- Podcast: Elisha Wiesel on His Father’s Jewish and Zionist Legacy

- Podcast: Antonio Garcia Martinez on Choosing Judaism as an Antidote to Secular Modernity

- Podcast: Haviv Rettig Gur on the Jewish Agency in 2021

- Podcast: Yedidya Sinclair on Israel’s Shmitah Year

- Podcast: Peter Kreeft on the Philosophy of Ecclesiastes

- Podcast: Dara Horn on Why People Love Dead Jews

- Podcast: Elliot Kaufman on the Crown Heights Riot, 30 Years Later

- Podcast: Cynthia Ozick on Her New Novel Antiquities

- Podcast: Jenna & Benjamin Storey on Why Americans Are So Restless

- Podcast: Kenneth Marcus on How the IHRA Definition of Anti-Semitism Helps the Government Protect Civil Rights

- Podcast: Nir Barkat on a Decade of Governing the World’s Most Spiritual City

- Podcast: Yehoshua Pfeffer on How Haredi Jews Think About Serving in the IDF

- Podcast: Shalom Carmy on Jewish Understanding of Human Suffering

- Podcast: Dru Johnson on Biblical Philosophy

- Podcast: David Rozenson on How His Family Escaped the Soviet Union and Why He Chose to Return

- Podcast: Matti Friedman How Americans Project Their Own Problems onto Israel

- Podcast: Benjamin Haddad on Why Europe Is Becoming More Pro-Israel

- Podcast: Seth Siegel on Israel’s Water Revolution

- Podcast: Michael Doran America’s Strategic Realignment in the Middle East

- Podcast: Sohrab Ahmari on Why Americans Must Recover the Sabbath

- Podcast: Shlomo Brody on Reclaiming Biblical Social Justice

- Podcast: Christine Rosen on the New Crime Wave and Its Consequences

- Podcast: Jonathan Schanzer on the Palestinians’ Political Mess

- Podcast: Meena Viswanath on How the Duolingo App Became an Unwitting Arbiter of Modern Jewish Identity

- Podcast: Sean Clifford on the Israeli Company Making the Internet Safe for American Families

- Podcast: Mark Gerson on How the Seder Teaches Freedom Through Food

- Podcast: Daniel Gordis on the Israeli Supreme Court’s New Conversion Ruling

- Podcast: Gil & Tevi Troy’s Non-Negotiable Judaisms

- Podcast: Richard Goldberg on How Iran Is Already Testing the Biden Administration

- Podcast: Shany Mor on What Makes America’s Peace Processors Tick

- Podcast: Yehoshua Pfeffer on How the Coronavirus Prompted Him to Rethink the Relationship between Haredim and Israeli Society

- Podcast: Gerald McDermott & Derryck Green on How Biblical Ideas Can Help Bridge America’s Racial Divide

- Podcast: Emmanuel Navon on Jewish Diplomacy from Abraham to Abba Eban

- Podcast: Michael Oren on Writing Fiction and Serving Israel

- Podcast: Joel Kotkin Thinks about God and the Pandemic

- Podcast: Dore Gold on the Strategic Importance of the Nile River and the Politics of the Red Sea

- Podcast: Yuval Levin Asks How Religious Minorities Survive in America—Then and Now

- Podcast: Mark Gottlieb on Rabbi Soloveitchik’s “Everlasting Hanukkah”

- Podcast: Ambassador Ron Dermer Looks Back on His Years in Washington

- Podcast: Richard Goldberg on the Future of Israeli-Saudi Relations

- Podcast: Matti Friedman on the Russian Aliyah—30 Years Later

- Podcast: Daniel Gordis on America, Israel, and the Sources of Jewish Resilience

- Podcast: John Podhoretz on 75 Years of Commentary

- Podcast: Michael McConnell on the Free Exercise of Religion

- Podcast: Ruth Wisse on Five Books Every Jew Should Read

- Podcast: Dan Senor on the Start-Up Nation and COVID-19

- Podcast: Reflections for the Days of Awe

- Podcast: Haviv Rettig Gur on Israel’s Deep State

- Podcast: Ruth Wisse & Hillel Halkin on the Authors Who Created Modern Hebrew Literature

- Podcast: Gil Troy on Never Alone

- Podcast: Jared Kushner on His Approach to Middle East Diplomacy

- Podcast: Ambassador Ron Dermer on the Israel-U.A.E. Accord

- Podcast: Micah Goodman on Politics, Power, and Kingship in Deuteronomy

- Podcast: Michael Doran on China‘s Drive for Middle Eastern Supremacy

- Podcast: Peter Berkowitz on Unalienable Rights, the American Tradition, and Foreign Policy

- Podcast: Wilfred McClay on the Historic Jewish-Christian Rapprochement

- Podcast: Amos Yadlin on the Explosions Rocking Iran

- Podcast: Jason Bedrick on School Choice, Religious Liberty, and the Jews

- Podcast: Meir Soloveichik on the Genius of Rabbi Norman Lamm

- Podcast: Tara Isabella Burton on Spirituality in a Godless Age

- Podcast: Gary Saul Morson on “Leninthink“

- Podcast: David Wolpe on The Pandemic and the Future of Liberal Judaism

- Podcast: Chaim Saiman on the “Zoom Seder“ and Its Discontents

- Podcast: Leon Kass on Reading Exodus and the Formation of the People of Israel

- Podcast: Einat Wilf on the West‘s Indulgence of Palestinian Delusions

- Podcast: Matti Friedman—The End of the Israeli Left?

- Podcast: Yehoshua Pfeffer on Haredi Society and the COVID-19 Crisis

- Podcast: Menachem Wecker on Yoga and Idolatry

- Podcast: Moshe Koppel on How Israel‘s Perpetual Election Came to an End

- Podcast: Michael Doran on Coronavirus in Iran

- Podcast: Yossi Klein Halevi on the Transformation of Israeli Music

- Podcast: Richard Goldberg on the Future of Iran Policy

- Podcast: Rafael Medoff on Franklin Roosevelt, Rabbi Stephen Wise, and the Holocaust

- Podcast: Eugene Kontorovich on the Trump Peace Plan

- Podcast: Mark Gottlieb on Jewish Sexual Ethics

- Podcast: Michael Avi Helfand on Religious Freedom, Education, and the Supreme Court

- Podcast: Joshua Berman on Biblical Criticism, Faith, and Integrity

- Podcast: Ruth Wisse on What Saul Bellow Saw

- Podcast: Daniel Cox on Millennials, Religion, and the Family

- Podcast: Yuval Levin on Rebuilding American Institutions

- Podcast: Neil Rogachevsky on Israeli Electoral Reform

- Podcast: Yuval Levin on the Remarkable Legacy of Gertrude Himmelfarb

- Podcast: Best of 2019 at the Tikvah Podcast

- Podcast: Arthur Herman on China and the U.S.-Israel “Special Relationship”

- Podcast: Walter Russell Mead on Israel and American Foreign Policy

- Podcast: Senator Joseph Lieberman on American Jews and the Zionist Dream

- Podcast: Eugene Kontorovich on America and the Settlements

- Podcast: David Makovsky—What Can We Learn from Israel’s Founders?

- Podcast: Christine Rosen on Thinking Religiously about Facebook

- Podcast: Jacob Howland—The Philosopher Who Reads the Talmud

- Podcast: Dru Johnson, Jonathan Silver, & Robert Nicholson on Reviving Hebraic Thought

- Podcast: Thomas Karako on the U.S., Israel, and Missile Defense

- Podcast: David Bashevkin on Sin and Failure in Jewish Thought

- Podcast: Matti Friedman on Israel, the Mizrahi Nation

- Podcast: Micah Goodman on Shrinking the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict

- Podcast: Jack Wertheimer on the New American Judaism – Part III

- Podcast: Meir Soloveichik on the Meaning of Kashrut

- Podcast: Avi Weiss on the AMIA Bombing Cover-Up

- Podcast: Jack Wertheimer on the New American Judaism – Part II

- Podcast: Jack Wertheimer on the New American Judaism – Part I

- Podcast: Jeremy Rabkin on Israel and International Law

- Podcast: Yehoshua Pfeffer on Haredi Politics and Culture

- Podcast: Mona Charen on Sex, Love, and Where Feminism Went Wrong

- Podcast: Dara Horn on Eternal Life

- Podcast: David Evanier on the Rosenbergs, Morton Sobell, and Jewish Communism

- Podcast: Michael Doran on America’s Standoff with Iran

- Podcast: Daniel Krauthammer on His Father’s Jewish Legacy

- Podcast: Yaakov Katz on Shadow Strike

- Podcast: Annika Hernroth-Rothstein on the Miracle of Jewish Continuity

- Podcast: Menachem Wecker on What’s Wrong with the Jewish Museum

- Podcast: Francine Klagsbrun on Golda Meir—Israel’s Lioness

- Podcast: Jonathan Neumann on the Left, the Right, and the Jews

- Podcast: Matti Friedman on Israel’s First Spies

- Podcast: Dovid Margolin on the Rebbe’s Campaign for a Moment of Silence

- Podcast: Scott Shay on Idolatry, Ancient and Modern

- Podcast: Joshua Berman on Whether the Exodus Really Happened

- Podcast: Daniel Gordis on the Rift Between American and Israeli Jews

- Podcast: Nicholas Gallagher on Jewish History and America’s Immigration Crisis

- Podcast: Special Envoy Elan Carr on America’s Fight against Anti-Semitism

- Podcast: Malka Groden on the Jewish Family and America’s Adoption Crisis

- Podcast: Eugene Kontorovich Explains Congress’s Effort to Counter BDS

- Podcast: David Wolpe on the Future of Conservative Judaism

- Podcast: Michael Doran on America’s Allies and America’s Enemies

- Podcast: Jonah Goldberg on Marx’s Jew-Hating Conspiracy Theory

- Podcast: Ambassador Danny Danon Goes on Offense at the U.N.

- Podcast: A New Year at the Tikvah Podcast

- Podcast: The Best of 2018

- Podcast: Jacob J. Schacter on Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik and the State of Israel

- Podcast: Chaim Saiman on the Rabbinic Idea of Law

- Podcast: Daniel Polisar on Herzl’s “The Menorah”

- Podcast: Yehoshua Pfeffer on Haredi Conservatism

- Podcast: Leon Kass on His Life and the Worthy Life

- Podcast: Clifford Librach on the Reform Movement and Jewish Peoplehood

- Podcast: Michael Doran on Theology, Zionism, and American Foreign Policy

- Podcast: Sohrab Ahmari on Sex, Desire, and the Transgender Movement

- Podcast: Yoram Hazony on the Bible’s Political Teaching

- Podcast: John Podhoretz on the Best and Worst of Jewish Cinema

- Podcast: Jamie Kirchick on Europe’s Coming Dark Age

- Special Podcast: Introducing Kikar – Elliott Abrams on Hamas, Gaza, and the Case for Jewish Power

- Podcast: Ruth Wisse on the Nature and Functions of Anti-Semitism

- Podcast: Jeffrey Saks on Shmuel Yosef Agnon

- Podcast: Samuel Goldman on Christian Zionism in America

- Podcast: Martin Kramer on Ben-Gurion, Borders, and the Vote That Made Israel

- Podcast: Russ Roberts on Hayek, Knowledge, and Jewish Tradition

- Podcast: Yossi Klein Halevi on Moving In and Out of Extremism

- Podcast: Charles Freilich on the U.S.-Israel “Special Relationship”

- Podcast: Jeffrey Salkin on ”Judaism Beyond Slogans”

- Podcast: Erica Brown on Educating Jewish Adults

- Podcast: Mark Dubowitz on the Future of the Iran Deal

- Podcast: Greg Weiner on Moynihan, Israel, and the United Nations

- Podcast: Daniel Polisar on Nationhood, Zionism, and the Jews

- Podcast: Jon Levenson on the Danger and Opportunity of Jewish-Christian Dialogue

- Podcast: Leora Batnitzky on the Legacy of Leo Strauss

- Podcast: Wilfred McClay on America’s Civil Religion

- Podcast: Robert Nicholson on Evangelicals, Israel, and the Jews

- Podcast: Charles Small on ”The Changing Face of Anti-Semitism”

- Podcast: Daniel Mark on Judaism and Our Postmodern Age

- Podcast: Ruth Wisse on the Perversity of Brilliance

- Podcast: Daniel Troy on ”The Burial Society”

- Podcast: Matthew Continetti on William F. Buckley, the Conservative Movement, and Anti-Semitism

- Podcast: Jonathan Sacks on Creative Minorities

- Podcast: Elliott Abrams on ”Dictatorships and Double Standards”

- Podcast: Jay Lefkowitz on His Life in the Arena

- Podcast: Michael Doran on America’s Middle East Strategy

- Podcast: Gabriel Scheinmann on Bombing the Syrian Reactor

- Podcast: Elliott Abrams on His Calling and Career

- Podcast: Jeffrey Bloom on Faith and America’s Addiction Crisis

- Podcast: Gil Student on the Journey into Orthodoxy

- Podcast: Meir Soloveichik on ”L’Chaim and Its Limits”

- Podcast: Michael Makovsky on Churchill and the Jews

- Debating Zionism: A Lecture Series with Dr. Micah Goodman

- Podcast: Neil Rogachevsky on the Story Behind Oslo

- Podcast: Mark Gottlieb on Jewish Education

- Podcast: Mitchell Rocklin on Jewish-Christian Relations

- Podcast: Liel Leibovitz on the Jewish Poetry of Leonard Cohen

- Podcast: Ruth Wisse on Tevye the Dairyman

- Podcast: Samuel Goldman on Religion, State, and the Jews

- Podcast: Leon Kass on the Ten Commandments

- Podcast: Ruth Wisse on Cynthia Ozick’s ”Innovation and Redemption”

- Podcast: Yossi Klein Halevi on Ze’ev Jabotinsky’s “The Iron Wall“

- Podcast: Tevi Troy on the Politics of Tu B’Shvat

- Podcast: Jay Lefkowitz & Mitchell Rocklin on the Jewish Vote

- Podcast: Yuval Levin on the Long Way to Liberty

- Podcast: Ruth Wisse on Sartre and Anti-Semitism

- Podcast: Edward Rothstein on Jerusalem Syndrome at the Met

- Podcast: Matthew Continetti on Irving Kristol’s Theological Politics

- Podcast: Meir Soloveichik on King David

- Podcast: R.R. Reno on ”Faith in the Flesh”

- Podcast: Arthur Herman on Why Everybody Loves Israel

- Podcast: Peter Berkowitz on a Liberal Education and Its Betrayal

- Podcast: Meir Soloveichik on Rembrandt, Tolkien, and the Jews

- Podcast: Yoram Hazony on Nationalism and the Future of Western Freedom

- Podcast: Jason Bedrick on Jewish Day Schools and School Choice

- Podcast: Allan Arkush on Ahad Ha’am and “The Jewish State and Jewish Problem”

- Podcast: Bret Stephens on the Legacy of 1967 and the U.S.-Israel Relationship

- Podcast: Jay Lefkowitz on Social Orthodoxy

- Podcast: Norman Podhoretz on Jerusalem and Jewish Particularity

- Podcast: Michael Doran on Western Elites and the Middle East

- Podcast: Ruth Wisse on Campus Anti-Semitism

- Podcast: Meir Soloveichik on ”Confrontation”

- Podcast: Yuval Levin on Religious Liberty

- Podcast: Elliott Abrams on Israel and American Jews