Last week on Shabbat, synagogues around the world turned the page from parshat Yitro (Exodus 18:1 – 20:23) to parshat Mishpatim (Exodus 21:1 – 24:18). The steady flow of narrative, beginning with The Beginning and moving through Noah, the Patriarchs, the birth of Moses and his call from the burning bush, the plagues and exodus from Egypt, the arrival at Sinai and the epiphany that sounds forth in the Decalogue – this current of sublime narrative gives way to lengthy descriptions of law and ritual. How should we think about this pivot in style? What does it reveal about the deep character of Judaism’s sacred text and about Judaism itself? In this Jewish Review of Books essay, Hillel Halkin offers his characteristically erudite and luminous perspective.

Last week on Shabbat, synagogues around the world turned the page from parshat Yitro (Exodus 18:1 – 20:23) to parshat Mishpatim (Exodus 21:1 – 24:18). The steady flow of narrative, beginning with The Beginning and moving through Noah, the Patriarchs, the birth of Moses and his call from the burning bush, the plagues and exodus from Egypt, the arrival at Sinai and the epiphany that sounds forth in the Decalogue – this current of sublime narrative gives way to lengthy descriptions of law and ritual. How should we think about this pivot in style? What does it reveal about the deep character of Judaism’s sacred text and about Judaism itself? In this Jewish Review of Books essay, Hillel Halkin offers his characteristically erudite and luminous perspective.

Law in the Desert

By Hillel Halkin | Originally Published in the Jewish Review of Books, Spring 2011

Talk of failed New Year’s resolutions! Three or four times over the years, come Rosh Hashanah, I’ve promised myself that this year, this year, I’ll study at home each week, with its standard commentaries, the parshat ha-shavu’a, the weekly Torah reading recited in synagogue on the Sabbath. Three or four times, I’ve started out a few weeks later with high hopes. Three or four times, I’ve worked my way through the ten weekly readings of Genesis and the first five of Exodus. Three or four times, I’ve stopped there. Studying the weekly Torah reading with its commentaries is an old Jewish custom, and many Jews—most, unlike myself, regular synagogue-goers—repeat the entire 52-week cycle of the Chumash, the Five Books of Moses, year after year. Although different annotated editions of the Chumash have different commentaries, the more complete sets include, at a minimum, the 2nd-century Aramaic translation of the Bible known as Targum Onkelos; the 11th-century commentary of Rabbi Shlomo Yitzhaki or Rashi; the 12th-century commentary of Rabbi Abraham ibn Ezra, and the 13th-century commentary of Rabbi Moses ben Nachman, also known as Nachmanides or “the Ramban.” Together with the voluminous corpus of the Midrash upon which they frequently draw, these are the main pillars of Jewish biblical exegesis, on which all subsequent commentators have built.

Upcoming Related Events & Courses:

Is Judaism a Religion? (Thursday, February 20, 2014 at 5:30pm)

with Leora Batnitzky

Abraham Joshua Heschel and the Call of Transcendence (Tuesday, February 25, 2014 at 5:30pm)

with Shai Held

The Jewish Idea of God (May 27, 2014 – June 1, 2014)

with Micah Goodman and Clifford Orwin

The Tikvah Summer Fellowship on Jewish Thought & Citizenship (July 27, 2014 – August 8, 2014)

Past Related Courses:

The Biblical View of Human Nature (Fall 2013)

with Eric Cohen, Alan Mittleman, and Meir Soloveichik

Each has its distinctive traits. The Targum, though on the whole highly literal, occasionally introduces free rabbinic interpretations into the text. Rashi, a meticulous Hebraist, is pietistic in outlook and a faithful transmitter of rabbinic tradition. Ibn Ezra, no less scrupulous a grammarian, is a rationalist with a preference for naturalistic and sometimes philosophical explanations. The Ramban likes to rely on his predecessors for the plain meanings of verses while focusing on broader contextual issues.

They complement one another. Their interplay isn’t always explicit. “Your brother has come in deceit and taken your blessing,” says Isaac to Esau in the sixth weekly reading of Genesis upon realizing that he has been tricked by Jacob. Onkelos, like the ancient rabbis, is disturbed by this—how can one revered Patriarch call another a deceiver?—and translates the Hebrew be-mirma, “in deceit,” as the Aramaic be-chukhma, “with wisdom.” Rashi echoes Onkelos without citing him. Ibn Ezra demurs without mentioning either man. “He told a lie,” he says tersely of Jacob, tacitly rebuking Rashi and Onkelos for whitewashing the text. The Ramban seeks to adjudicate. Yes, he says, Isaac does call Jacob a deceiver—but Isaac realizes the deceit is justifiable, having had the insight that Jacob, though not his own choice, is God’s, thus making Jacob a wise deceiver.

The Patriarchs! Often I have thought of them as great, lawless spirits taken captive by moralistic minds. Of course Jacob lies. He has to, precisely because his father does not have the insight the Ramban attributes to him. If anyone has it, it’s Jacob’s mother Rebecca, who masterminds the deceit. Jacob goes along with her willingly. He knows that the stakes—the legacy of the blessing first given by God to Abraham—are too high to allow for the rules of fairness. He grasps the magnitude of this legacy better than does Esau and so is worthier of it. In Genesis, the worthiest strive to fulfill a destiny of whose grandeur they are conscious even if they, too, do not fully comprehend it.

But Esau is himself a wonderful character—wonderful in grief when he cries out, “Bless me, Father, too,” and wonderful in forbearance when he and Jacob meet again years later. The rabbis, painting him in dark colors to highlight Jacob’s virtue, begrudge him any acknowledgment of this. Does the Bible tell us he was a capable fellow, “a man skilled in hunting”? “Hunting,” writes Rashi, conveys Esau’s shameless stalking of his father’s favors. Did he sell his birthright because he came home one day “weary” and desperate for refreshment? He was weary of all the murders he had committed. Drawn with great sympathy by the biblical text, he gets none from the classical commentators.

They flatten the text, these commentators, so as to re-elevate it on their own terms. I preferred my Patriarchs to theirs: lawless, unbridled, freely camping and decamping, putting up and taking down their tents; always on the move with their wives, their children, their concubines, their flocks and camels, their bitter family quarrels passed down from generation to generation; always restlessly seeking, carrying with them the destiny not fully understood. Abraham, the reckless gambler; timid yet tenacious Isaac; wily Jacob, tricking and being tricked; suave, diplomatic Joseph, lowering the curtain on Genesis with a happy ending just when it has come to seem the most tragic of books; Joseph, the divine impresario!

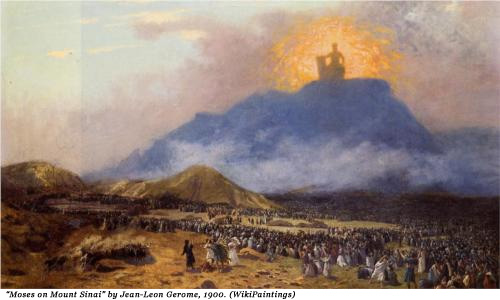

The curtain stays down for hundreds of years. When it rises again, the Patriarchs’ descendants are slaves in Egypt, ignorant of the legacy over which their ancestors fought. Moses appears—impetuous, self-doubting, unyielding, long-suffering Moses! He encounters the God of his forefathers. He and his brother Aaron confront Pharaoh. They inflict ten plagues on the Egyptians. They lead the Israelites to a mountain in the desert. Moses ascends it to receive the Law. “And Mount Sinai was all in smoke because the Lord came down on it in fire, and its smoke went up like the smoke from a kiln, and the whole mountain trembled greatly.” Onkelos, anxious as always to avoid physicalizing God, translates “came down on it” as “was revealed on it.” Rashi, having no such compunctions, tells us that God spread the sky over the mountain “as though covering a bed with a sheet” and lowered His throne onto it. Ibn Ezra remarks that Mount Sinai only trembled metaphorically. The Ramban explains that the Israelites did not see God descend in the fire but heard His voice saying, “I am the Lord your God . . . You shall have no other God beside me . . . You shall make no graven image of what is in the heavens above or on the earth below . . .”

It’s a page-turner, the parshat ha-shavu’a. I can’t wait for the next installment.

It comes. It’s called Mishpatim, “Laws.” It begins:

These are the laws you shall set before them. Should you buy a Hebrew slave, six years he shall serve and in the seventh he shall go free . . . And should an ox gore a man or a woman and they die, the ox shall surely be stoned and its flesh shall not be eaten, and the ox’s owner is clear . . . And should a man open a pit, or should a man dig a pit and not cover it and an ox or donkey fall in, the owner of the pit shall pay silver, and the carcass shall be his . . .

Next comes Terumah, “Donation.” It concerns the construction of the Tabernacle. It begins:

And the Lord spoke to Moses, saying: ‘Speak to the Israelites, that they take me a donation from every man . . . And this is the donation you shall take from them: gold and silver and bronze and indigo and purple and crimson and linen and goat hair and reddened ram skins and ocher-dyed skins and acacia wood . . .

After Terumah comes Tetzaveh, “You Shall Command.” It’s about the garments and sacrifices of the priests serving in the Tabernacle. It begins:

And you shall command the Israelites . . . and these are the garments they shall make: breastplate and ephod and robe and checkwork tunic, turban, and sash.

So this is the legacy! The grand narrative flow of Genesis and the first half of Exodus is over, though it still will burst forth in trickles here and there. It couldn’t have happened soon enough for Rashi. In his first comment on the first verse of Genesis he approvingly quotes the 4th-century Rabbi Yitzhak as saying that little would have been lost had the Bible started in the middle of Exodus, since “the crux of the Torah is only its commandments.”

Three or four times over the years, I reached the commandments. Three or four times, I got no further.

Last Rosh Hashanah, I resolved, after a long hiatus, to try again. I’m now at the end of Exodus and going strong. What made this year different? In part, my deciding to read the biblical text not in Hebrew but in the Latin Vulgate of the Christian church father Jerome. This added the stimulation of novelty.

Jerome translated the Bible while living in Palestine in the late 4th and early 5th centuries. An accomplished author in his own right, he studied Hebrew and Aramaic and regularly consulted Onkelos’ Targum; the Greek Septuagint (a Jewish translation of the Bible, the world’s first, done in Alexandria in the 3rd and 2nd centuries B.C.E.), and diverse rabbinic sources. Even more faithful than the Targum to the literal meaning of the biblical text, he was far freer with its form and took frequent liberties with its Hebrew syntax, whose extreme simplicity, with its repetitive reliance on short, independent clauses linked by paratactic “and’s,” fell short of his standards of Latin elegance. Often he subordinated clause to clause, as we do in English with all our “when’s,” “while’s,” “before’s,” and “during’s” that biblical Hebrew commonly eschews.

Jerome translated the legal and ritual sections of the Chumash out of a sense of duty; he could not but have been, I suspect, rather bored by them. While they, too, were a part of God’s word, they were the part that God had abrogated. Both Jerome’s Christian faith and his taste in prose would have inclined him more to the structured rhetoric of a Pauline epistle like Romans that declares:

Now we know that whatsoever things the Law says, it says to those who are under the Law, that every mouth may be stopped and all the world may become guilty before God. Therefore by the deeds of the Law there shall no flesh be justified in His sight, for by the Law is the knowledge of sin.

Dutiful Jerome, laboring faithfully through the laws of goring oxen, the measurements of the Tabernacle, and the vestments of its priests when they only led to the knowledge of sin!

Not that Paul was against laws. His epistles counsel adherence to those of Rome. But those were the laws of secular authority. Breaking them made one a criminal in the eyes of the state, not a sinner in the eyes of God. God had not promulgated them. He had promulgated the Law given at Sinai—and He had done so, paradoxically, knowing that its statutes were too numerous and complicated to be obeyed, so that anyone seeking to do so would be ultimately reduced to a helpless sense of his inability to perform God’s will. This, as Paul saw it, was the Law’s whole purpose: to produce in its adherents an overwhelming consciousness of sin, alien to the pagan world, that would compel them, followed by the rest of humanity, to throw themselves on the mercy of God’s grace as manifested through the son sent to atone for them.

I’ve always sympathized with Paul. He was raised, as I was, in the world of Jewish observance, and while he felt too cramped by it to remain in it, he was too attached to it to let go of it. He longed to link up with the rest of humanity while remaining the Jew that he was, and by repudiating the Law in the name of the Law he found a brilliant if tortured way of doing so. Long before Spinoza, he was the prototype of a certain kind of modern Jewish intellectual.

As a child, I, too, knew the difference between the laws of Rome and the laws of God. When I was 6 or 7 years old, sent by my mother to buy a newspaper, I took two papers from a pile at the stand by mistake, while paying only for one; but although I lived for a while in great fear of being arrested, I got over it as soon as I realized that my crime had gone unnoticed. It was different when I unwittingly placed a meat fork in the dairy silverware drawer in our kitchen. Then I had a consciousness of sin, which lasted longer. God was no kiosk owner.

All around me were sins waiting to be committed. If I forgot to say my bedtime prayers, I had sinned. If I unthinkingly switched on a light on the Sabbath, I had sinned. I envied the Patriarchs who lived before the Law. Hadn’t Abraham served his guests milk and butter with their meat? That was why Rashi was in such a hurry to get past him to the commandments. Yet three or four times over the years, I groaned when I reached them. So must have Jerome. Haec sunt iudicia quae propones eis, these are the laws you shall set before them. I did not want them set before me.

The second half of Exodus can be read as a study in the institutionalization of religion. No longer a small roaming band to whom God can appear anywhere and at any time, the Israelites leave Egypt as twelve tribes. They need what any large group needs if it is not to degenerate into a mob: clear rules of conduct, recognized penalties for breaking them, established forms and places of worship, trained specialists to mediate between them and the divine. Mishpatim, Terumah, Tetzaveh: these lay the foundations for a code of civil behavior, a centralized cultus, a priestly class. They mark, in the biblical narrative, a transition from an era of spontaneity between man and man, and between man and God, to one of regulated order. This is necessary. It is part of God’s plan. But as with all institutionalizations of originally spontaneous relationships, one feels nostalgic for what has been lost.

It is part of God’s second plan. His first is to create in six days a world that is all good and let human beings made in His image run it independently. This works out badly. The first humans disobey Him and are driven from Eden. By the tenth generation, the generation of Noah, “God saw the earth and it was corrupt, for all flesh had corrupted its ways on the earth.”

God wipes out everything with a great flood and starts anew. This time He will do it differently. He will ignore most of the human race; it is too large, too unruly, for Him to work with. He will proceed slowly, methodically. And so He begins with a single individual, Abraham. Again and again He tests him to make sure He has chosen correctly, satisfied only by the last, pitiless trial of the sacrifice of Isaac. From there He moves on to a family, carefully winnowing it as it grows until it consists of twelve brothers. Taking time out to let their offspring multiply and be enslaved in Egypt, He is now ready for the next stage: He will take the descendants of these brothers out of bondage and make them a model people—”a kingdom of priests and a holy nation,” as He tells them when they are assembled before Him at Sinai. They will be His pilot project on earth. Once it succeeds, He can extend it to the rest of humanity.

A model people needs model laws. God goes about it pedagogically, starting with the laws that He knows will be of greatest interest. As the Ramban puts it: “God began with the laws of the Hebrew slave because freeing him in the seventh year was a reminder of the exodus from Egypt.” More than a reminder: a promise to an anxious people that it will not be re-enslaved by the more powerful of its own brothers. One imagines the stir in the desert. Six years of servitude and no more! So this is law! Real slaves have no laws but the whims of their masters.

There follow laws of property, laws of damages and restitution, laws of theft and murder, laws of sexual relationships: the basic norms that a functional society must have. All else is in abeyance. Moses is on the mountain receiving the Law, and we, the Bible’s readers, are given a preview of it while the worried Israelites camped below await Moses’ return. We know the Law’s contents before they do.

The narrative only resumes with the weekly reading of Ki Tisa. Afraid that Moses has abandoned them and left them leaderless in the desert, the Israelites say to Aaron, “Rise up, make us gods that will go before us, for this man Moses who brought us up from the land of Egypt, we do not know what has happened to him.” And so Aaron collects their gold jewelry and fashions from it a calf—a graven image—and the people worship it and revel around it. High on the mountain, Moses is told by God, “Go, go down, for your people, which you have brought out of Egypt, has been corrupted.” Moses descends after first persuading God not to exterminate the Israelites as He threatens to; sees them dancing around the calf; angrily smashes the tablets of the Law that he is carrying, and commands the Levites to commit a punitive massacre in which three thousand people are killed.

“For your people has been corrupted,” ki shichet amkha: Rashi’s comment on the cutting “your”—that of a father who comes home to find his son misbehaving and tells his wife it’s her child, not his—is to assure us that God is not disassociating Himself from the Israelites, but scolding Moses for having permitted idolatrous heathen to join them and lead them astray. Well, that’s Rashi for you: always sticking up for the Jews. But why does neither he nor any of the other commentators in my Chumash point out that the verb shachet, to act corruptly, is the very same verb used in Genesis to describe the human race on the eve of the flood? Why does no one dwell on the obvious parallel between the two stories? In both, God sets out to create or recreate the world. In both, all goes well for a while. In both, the illusion of success soon collapses. In both, God resolves to destroy what He has done and begin again, the second time with Moses as a second Noah or Abraham. (“And now leave me be,” God tells Moses, “that my wrath may flare against them, and I will put an end to them, and I will make you a great nation.”) In both, God repents of His fury and offers its survivors an eternal pact—a promise not to repeat the flood, a reaffirmation of His covenant with Israel.

There must be commentators who have noticed this. The Zohar, itself a mystical commentary on the Chumash written shortly after the time of the Ramban, does notice it. When the Israelites sinned with the golden calf, it says, they fell from the heights of Sinai to the lower depths, for the same serpent that poisoned Adam poisoned them, so that gerimu mota le-khol alma, they brought, like Adam and Eve, death upon the whole world. The debacle at Sinai is a cosmic catastrophe, comparable only to the sin in Eden and its aftermath in reflecting as much on the incorrigibility of God’s optimism as on that of man’s waywardness.

I was wrong to think that the narrative flow of Exodus had ever stopped. Mishpatim, Terumah, and Tetzaveh were a continuation of it. They were needed, not only as a contretemps to create a sense of lapsed time, the forty days spent by Moses on the mountain, between two contiguous events, but because the drama lost much of its intensity without them. Their detail was necessary to illustrate the effort God had put into designing a Law flouted by His chosen people as soon as Moses turned his back on them—to illustrate the extent of His failure. His second attempt at forging order out of chaos, it is even more galling than the first, since the lesson learned from the first has not kept it from being repeated.

I was wrong to think that the narrative flow of Exodus had ever stopped. Mishpatim, Terumah, and Tetzaveh were a continuation of it. They were needed, not only as a contretemps to create a sense of lapsed time, the forty days spent by Moses on the mountain, between two contiguous events, but because the drama lost much of its intensity without them. Their detail was necessary to illustrate the effort God had put into designing a Law flouted by His chosen people as soon as Moses turned his back on them—to illustrate the extent of His failure. His second attempt at forging order out of chaos, it is even more galling than the first, since the lesson learned from the first has not kept it from being repeated.

This realization—parshat ha-shavu’a students would call it a chidush, a new way of looking at things—carried me excitedly through the last six Torah readings of Exodus that had always stymied me before. Suddenly, God’s effort needed to be understood. It was an integral part of the story. “And should a man open a pit, or should a man dig a pit and not cover it, and an ox or donkey fall in, the owner of the pit shall pay silver, and the carcass shall be his . . .” Did that mean that if an ox wandered onto my property and fell into a pit and was killed, I, the pit’s owner, was responsible?

No, said Rashi. My property was my property. The Torah was referring to a pit dug in the public domain.

But if I dig a pit in the public domain, how am I its owner?

By “owner,” Ibn Ezra explains, the Torah designates the pit’s user, since it must have been dug for some use.

Then I have no liability at all for a pit dug on my own property?

My parshat ha-shavu’a commentators weren’t clear about this. I looked at the 3rd-century-C.E. Mishnah, the earliest systematic explication of biblical law. Yes, said the first chapter of Bava Kama, the opening part of the treatise of Nezikin or “Damages”: if in digging a pit on my own property I cross the line separating it from the public domain, or from someone else’s property, anyone falling into it from the other side is my responsibility, too.

But it was more complicated than that. The 6th-century Gemara, the systematic explication of the Mishnah, stated that according to Rabbi Akiva, even if the pit was entirely on my property, I was still liable if I hadn’t made clear that trespassing was forbidden. Rabbi Ishmael disagreed. The Gemara’s discussion of their disagreement was long and intricate, and I had trouble following it.

Nor would following it in the Gemara have been enough to know the outcome. For that, I would have had to consult the Ge’onim, the 7th-to-11th-century Talmudic scholars of Babylonia; and after them, the Rishonim, the 11th-to-16th century scholars of North Africa and Europe; and after them the Acharonim, the scholars who came later—in short, the whole vast edifice of Jewish law. It suddenly towered above me, this edifice, in all its architectural immensity, dizzyingly tall—explication upon explication, disagreement upon disagreement, complication upon complication—and for the first time, though I had never gotten beyond its bottom floors, I felt that I grasped its full grandeur, the indomitable scope of its determination to make up for the golden calf. Century after century, the Jews had labored to convince God that He was right not to have given up on them at Sinai—that His pilot project could still work—that they would devote themselves to it endlessly, tirelessly, even if it took thousands of years—even if the rest of humanity went its own way in the meantime—even if the rest of humanity agreed that the Law only led to the knowledge of sin.

I’ve been thinking about the knowledge of sin.

Over the years I’ve been involved, sometimes alone and sometimes with others, in more court cases than I’d have liked to be. Nothing major. A case involving my father, then ill with Alzheimer’s, who was defrauded by his neighborhood grocer. A case involving a mobile phone antenna erected illegally opposite our home. A running battle with the town in which we live about building rights on our land. A consequent suit for damages filed by us. A fight with the local planning commission over a road it wanted to run through our and our neighbors’ property. Another fight to stop a nearby restaurant from blasting loud music into the night. All trivial stuff.

On the whole, the courts have performed creditably. I can’t complain too much about the judges. The depressing thing has been the deceit with which they’ve had to deal. Corrupt authorities. Secret, illicit deals. Law enforcers looking the other way. Manipulation of evidence. Lies on the witness stand. Suborning of witnesses.

I suppose it’s that way everywhere. Why wouldn’t it be? It’s only the laws of Rome. If you think you can get away with it, you break them. I’ve broken my share of them myself.

Wouldn’t we be better off with the Law of God? If every bribe taker and perjurer knew he was sinning?

Not that you can’t know you’re a sinner and still sin. And the laws of Mishpatim say not only “You shall take no bribe” and “You shall not bear false witness,” but also “Should a man sell his daughter as a slave girl, she shall not go free as the male slaves go free,” and “Whoever speaks profanely of his father and mother shall be put to death.” For all practical purposes, the rabbis abolished the death penalty even for murder, let alone for swearing at one’s parents, but that isn’t the point. The point is that knowing you’re a sinner in the eyes of the Law means believing the Law—all of it—is God’s. There may be nothing to keep you from obeying just those parts of it that you like, but if that’s your attitude, you won’t feel sinful when you disobey them. The laws of God and the laws of Rome are then two versions of the same thing.

I don’t say I believe the Law is God’s. I only say I’ve come to believe that if God had a plan for humanity, He would give it a Law, and he would not abrogate it as Paul thought He did.

I haven’t always been of that opinion. But neither was God. The first time around, He thought men could manage on their own and waited ten generations before deciding He was wrong.

A generation for Methusaleh was longer than it is for us, and even by our own paltry standards I haven’t lived through three. Still—so I found myself thinking this year while studying the parshat ha-shavu’a—I already am where God was after ten.

I’m not happy with that. I have an anarchistic streak. I’ve never liked being told what to do. I’ve always wanted to do the right thing because I wanted to, not because I had to. I’ve wanted to do it Paul’s way, without the Law, “for when the Gentiles, which have not the Law, do by nature the things contained in the Law, these, having not the Law, are a law unto themselves.”

Like the Patriarchs.

It’s a nice idea. It was clever of Paul to have thought of it. It just doesn’t work. It didn’t work in the days of Noah and it won’t work now. There isn’t enough of mankind that, having no Law, will do by nature the things contained in the Law. We need a sense of sin to bridle us. If it’s taken me most of a lifetime to realize that, then that’s what lifetimes must be for.

This week was Pekudei, the last Torah reading of Exodus. Before it came Vayakhel. Together they are two of the most tedious parshot ha-shavu’a in the Chumash. Vayakhel relates how the Israelites built the Tabernacle according to the instructions in Terumah; Pekudei, how they made the priests’ vestments according to the instructions in Tetzaveh. Both repeat the language of Terumah and Tetzaveh almost to a word. “And they shall make an Ark of acacia wood, two and a half cubits its length, and a cubit and a half its width, and a cubit and a half its height,” says Terumah. “And Bezalel made an Ark of acacia wood, two and a half cubits its length, and a cubit and a half its width, and a cubit and a half its height,” says Vayakhel. The commentators fall silent. What’s there to add?

But a chidush is a chidush—and now I read even Vayakhel and Pekudei with fresh eyes, starting with the former’s opening verses, which describe how the Israelites, called upon to donate “gold and silver and bronze and indigo and purple and crimson and linen and goat hair and reddened ram skins and ocher-dyed skins and acacia wood,” respond with such enthusiasm that Moses has to tell them to stop, there being already more than enough. If it occurred to any of the commentators in my Chumash that behind this outpouring of public-spiritedness was a consciousness of sin, they kept it to themselves. I can’t say it didn’t occur to me.

There is a cheerfulness in Vayakhel and Pekudei that would hardly have seemed possible a short time before when Moses dashed the Law to the ground. Everyone is bringing gifts to the Tabernacle; everyone is measuring, making, fitting. Bezalel runs around giving orders. We hear the sounds of saws and hammers; there is a smell of freshly cut lumber, the crisp colors of newly died fabrics.

And they made the boards for the Tabernacle, twenty boards for the southern end . . . And they made the curtain of indigo and purple and crimson, designer’s work they made it . . . And they made tunics of twisted linen, weaver’s work, for Aaron and his sons . . .

It’s like a huge stage set on which a multitude of workers is racing to get things done in time for the premiere.

The date arrives. It’s the anniversary of the exodus, the first day of the first month of its second year. Miraculously, everything is ready. The Tabernacle is standing. The Ark of the Covenant is in place. The showbread is on the table. The lamp in the Tent of Meeting is lit. The golden altar is ready for its offerings. Moses enters and offers up the burnt offering and the meal offering as commanded. The audience holds its breath.

And then it happens: “And cloud covered the Tent of Meeting and the glory of the Lord filled the Tabernacle.”

It’s a mini-Sinai, God’s glory in a cloud like fire in smoke. All that light and dark mixed together, the brightest sunshine and the blackest gloom!

“And the cloud went up from over the Tabernacle, the Israelites would journey onward in all their journeyings. And if the cloud did not go up, they would not journey onward until the day it went up. For the Lord’s cloud was over the Tabernacle by day, and fire by night was in it, before the eyes of all the house of Israel in all their journeyings.”

Explicit, says Jerome, liber Ellesmoth id est Exodus.

Bring on Leviticus.

About the Author

Hillel Halkin is a translator, essayist, and author of four books, the most recent of which is Yehuda Halevi (Schocken/Nextbook).

- Noah Rothman on Kamala Harris’s Views of Israel and the Middle East

- Avi Weiss on the AMIA Bombing 30 Years Later (Rebroadcast)

- Melanie Phillips on the British Election and the Jews

- Mark Cohn on the Reform Movement and Intermarriage

- Jeffrey Saks on the Genius of S.Y. Agnon

- Shlomo Brody on What the Jewish Tradition Says about Going to War

- Chaim Saiman on the Roots and Basis of Jewish Law (Rebroadcast)

- Elliott Abrams on American Jewish Anti-Zionists

- Andrew Doran on Why He Thinks the Roots of Civilization Are Jewish

- Haisam Hassanein on How Egypt Sees Gaza

- Asael Abelman on the History of “Hatikvah”

- Shlomo Brody on Jewish Ethics in War

- Ruth Wisse on the Explosion of Anti-Israel Protests on Campus

- Meir Soloveichik on the Politics of the Haggadah

- Yechiel Leiter on Losing a Child to War

- Yehoshua Pfeffer on Haredi Service in the Israeli Military

- Joseph Lieberman on American Jews and the Zionist Dream (Rebroadcast)

- Seth Kaplan on How to Fix America’s Fragile Neighborhoods

- Timothy Carney on How It Became So Hard to Raise a Family in America

- Jonathan Conricus on How Israeli Aid to Gaza Works

- Vance Serchuk on Ten Years of the Russia-Ukraine War

- Yehuda Halper on Maimonides the Physician

- Cynthia Ozick on the Story of a Jew Who Becomes a Tormentor of Other Jews

- Yehuda Halper on Guiding Readers to “The Guide of the Perplexed”

- Ray Takeyh on What Iran Wants

- Yehuda Halper on Maimonides and the Human Condition

- Hillel Neuer on How the Human-Rights Industry Became Obsessed with Israel

- Yehuda Halper on Where to Begin With Maimonides

- Our Favorite Conversations of 2023

- Matti Friedman on Whether Israel Is Too Dependent on Technology

- Ghaith al-Omari on What Palestinians Really Think about Hamas, Israel, War, and Peace

- Alexandra Orbuch, Gabriel Diamond, and Zach Kessel on the Situation for Jews on American Campuses

- Roya Hakakian on Her Letter to an Anti-Zionist Idealist

- Edward Luttwak on How Israel Develops Advanced Military Technology On Its Own

- Assaf Orion on Israel’s Initial Air Campaign in Gaza

- Bruce Bechtol on How North Korean Weapons Ended Up in Gaza

- Hay Eytan Cohen Yanarocak on Whether Hamas Doomed Israeli-Turkish Relations

- Michael Doran on Israel’s Wars: 1973 and 2023

- Ethan Tucker on the Jewish Duty to Recover Hostages

- Meir Soloveichik on What Jews Believe and Say about Martyrdom

- Yascha Mounk on the Identity Trap and What It Means for Jews

- Alon Arvatz on Israel’s Cyber-Security Industry

- Daniel Rynhold on Thinking Repentance Through

- Jon Levenson on Understanding the Binding of Isaac as the Bible Understands It

- Yonatan Jakubowicz on Israel’s African Immigrants

- Mordechai Kedar on the Return of Terrorism in the West Bank

- Ran Baratz on the Roots of Israeli Angst

- Dovid Margolin on Kommunarka and the Jewish Defiance of Soviet History

- Shlomo Brody on Capital Punishment and the Jewish Tradition

- Podcast: Dara Horn on Why People Love Dead Jews (Rebroadcast)

- Podcast: Izzy Pludwinski on the Art and Beauty of Hebrew Calligraphy

- Podcast: Joshua Berman on the Traumas of the Book of Lamentations

- Podcast: Meir Soloveichik on Ten Portraits of Jewish Statesmanship

- Podcast: Nathan Diament on Whether the Post Office Can Force Employees to Work on the Sabbath

- Podcast: Yaakov Amidror on Why He’s Arguing That Israel Must Prepare for War with Iran

- Podcast: Liel Leibovitz on the Return of Paganism

- Podcast: Rick Richman on History and Devotion

- Podcast: Yuval Levin on How America’s Constitution Might Help Solve Israel’s Judicial Crisis

- Podcast: Neil Rogachevsky & Dov Zigler on the Political Philosophy of Israel’s Declaration of Independence

- Podcast: Yehoshua Pfeffer on Israel’s Social Schisms and How They Affect the Judicial Reform Debate

- Podcast: Jonathan Schachter on What Saudi Arabia’s Deal with Iran Means for Israel and America

- Podcast: Peter Berkowitz & Gadi Taub on the Deeper Causes of Israel’s Internal Conflict

- Podcast: Jordan B. Gorfinkel on His New Illustrated Book of Esther

- Podcast: Malka Simkovich on God’s Maternal Love

- Podcast: Richard Goldberg on Recent Joint Military Exercises Between America and Israel

- Podcast: Russ Roberts on the Disappointment and the Promise of Prayer

- Podcast: Joshua Berman on Traveling to Biblical Egypt

- Podcast: Elliott Abrams on American Jews and the New Israeli Government

- Podcast: Carl Gershman on What the Jewish Experience Can Offer the Uighurs of China

- Podcast: Benjamin Netanyahu on His Moments of Decision

- Podcast: Maxim D. Shrayer on the Moral Obligations and Dilemmas of Russia’s Jewish Leaders

- Podcast: Ryan Anderson on Why His Think Tank Focuses on Culture and Not Just Politics

- Podcast: Simcha Rothman on Reforming Israel’s Justice System

- Podcast: Michael Doran on Iran’s Growing Military Dominance in the Middle East

- Podcast: Scott Shay on How BDS Crept into the Investment World, and How It Was Kicked Out

- Podcast: Haviv Rettig Gur on Netanyahu, Lapid, and Another Israeli Election

- Podcast: Yoav Sorek, David Weinberg, & Jonathan Silver on What Jewish Magazines Are For

- Podcast: Tony Badran Puts Israel’s New Maritime Borders with Lebanon into Context

- Podcast: George Weigel on the Second Vatican Council and the Jews

- Podcast: Shay Khatiri on the Protests Roiling Iran

- Podcast: Meir Soloveichik on Jerusalem’s Enduring Symbols

- Podcast: Daniel Polisar on the First Zionist Congress, 125 Years Later

- Podcast: Hussein Aboubakr on the Holocaust in the Arab Moral Imagination

- Podcast: Jonathan Schanzer on Israel’s Weekend War against Islamic Jihad

- Podcast: Yair Harel on Haim Louk’s Masterful Jewish Music

- Podcast: Jacob J. Schacter on Why So Many Jewish Soldiers Are Buried Under Crosses, and What Can Be Done About It

- Podcast: Robert Nicholson on the Changing Face of Evangelical Zionism

- Podcast: Daniel Gordis & Asael Abelman on the Personality of the New Jew

- Podcast: Douglas Murray on the War on the West

- Podcast: Jeffrey Woolf on the Political and Religious Significance of the Temple Mount

- Podcast: Zohar Atkins on the Contested Idea of Equality

- Podcast: Steven Smith on Persecution and the Art of Writing

- Podcast: Jon Levenson on the Moral Force of the Book of Ruth

- Podcast: Tony Badran on How Hizballah Wins, Even When It Loses

- Podcast: John Podhoretz on Midge Decter’s Life in Ideas

- Podcast: Motti Inbari on the Yemenite Children Affair

- Podcast: Christine Emba on Rethinking Sex

- Podcast: Shany Mor on How to Understand the Recent Terror Attacks in Israel

- Podcast: Abraham Socher on His Life in Jewish Letters and the Liberal Arts

- Podcast: Ilana Horwitz on Educational Performance and Religion

- Podcast: David Friedman on What He Learned as U.S. Ambassador to Israel

- Podcast: Andy Smarick on What the Government Can and Can’t Do to Help American Families

- Podcast: Aaron MacLean on Deterrence and American Power

- Podcast: Ronna Burger on Reading Esther as a Philosopher

- Podcast: Dovid Margolin on Jewish Life in War-Torn Ukraine

- Podcast: Vance Serchuk on the History and Politics Behind Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine

- Podcast: Ruth Wisse on the Stories Jews Tell

- Podcast: Yossi Shain on the Israeli Century

- Podcast: Michael Doran on the Most Strategically Valuable Country You’ve Never Heard Of

- Podcast: Mitch Silber on Securing America’s Jewish Communities

- Podcast: Jesse Smith on Transmitting Religious Devotion

- Podcast: Matti Friedman on China’s New Haifa Port

- Podcast: Jay Greene on Anti-Semitic Leanings Among College Diversity Administrators

- Podcast: Our Favorite Broadcasts of 2021

- Podcast: Three Young Jews on Discovering Their Jewish Purposes

- Podcast: Annie Fixler on Cyber Warfare in the 21st Century

- Podcast: Victoria Coates on the Confusion in Natanz

- Podcast: Judah Ari Gross on Why Israel and Morocco Came to a New Defense Agreement

- Podcast: Michael Avi Helfand on Jewish Life and Law at the Supreme Court

- Podcast: Nicholas Eberstadt on What Declining Birthrates Mean for the Future of the West

- Podcast: Suzy Weiss on the Childless Lives of Young American Women

- Podcast: Michael Eisenberg on Economics in the Book of Genesis

- Podcast: Elisha Wiesel on His Father’s Jewish and Zionist Legacy

- Podcast: Antonio Garcia Martinez on Choosing Judaism as an Antidote to Secular Modernity

- Podcast: Haviv Rettig Gur on the Jewish Agency in 2021

- Podcast: Yedidya Sinclair on Israel’s Shmitah Year

- Podcast: Peter Kreeft on the Philosophy of Ecclesiastes

- Podcast: Dara Horn on Why People Love Dead Jews

- Podcast: Elliot Kaufman on the Crown Heights Riot, 30 Years Later

- Podcast: Cynthia Ozick on Her New Novel Antiquities

- Podcast: Jenna & Benjamin Storey on Why Americans Are So Restless

- Podcast: Kenneth Marcus on How the IHRA Definition of Anti-Semitism Helps the Government Protect Civil Rights

- Podcast: Nir Barkat on a Decade of Governing the World’s Most Spiritual City

- Podcast: Yehoshua Pfeffer on How Haredi Jews Think About Serving in the IDF

- Podcast: Shalom Carmy on Jewish Understanding of Human Suffering

- Podcast: Dru Johnson on Biblical Philosophy

- Podcast: David Rozenson on How His Family Escaped the Soviet Union and Why He Chose to Return

- Podcast: Matti Friedman How Americans Project Their Own Problems onto Israel

- Podcast: Benjamin Haddad on Why Europe Is Becoming More Pro-Israel

- Podcast: Seth Siegel on Israel’s Water Revolution

- Podcast: Michael Doran America’s Strategic Realignment in the Middle East

- Podcast: Sohrab Ahmari on Why Americans Must Recover the Sabbath

- Podcast: Shlomo Brody on Reclaiming Biblical Social Justice

- Podcast: Christine Rosen on the New Crime Wave and Its Consequences

- Podcast: Jonathan Schanzer on the Palestinians’ Political Mess

- Podcast: Meena Viswanath on How the Duolingo App Became an Unwitting Arbiter of Modern Jewish Identity

- Podcast: Sean Clifford on the Israeli Company Making the Internet Safe for American Families

- Podcast: Mark Gerson on How the Seder Teaches Freedom Through Food

- Podcast: Daniel Gordis on the Israeli Supreme Court’s New Conversion Ruling

- Podcast: Gil & Tevi Troy’s Non-Negotiable Judaisms

- Podcast: Richard Goldberg on How Iran Is Already Testing the Biden Administration

- Podcast: Shany Mor on What Makes America’s Peace Processors Tick

- Podcast: Yehoshua Pfeffer on How the Coronavirus Prompted Him to Rethink the Relationship between Haredim and Israeli Society

- Podcast: Gerald McDermott & Derryck Green on How Biblical Ideas Can Help Bridge America’s Racial Divide

- Podcast: Emmanuel Navon on Jewish Diplomacy from Abraham to Abba Eban

- Podcast: Michael Oren on Writing Fiction and Serving Israel

- Podcast: Joel Kotkin Thinks about God and the Pandemic

- Podcast: Dore Gold on the Strategic Importance of the Nile River and the Politics of the Red Sea

- Podcast: Yuval Levin Asks How Religious Minorities Survive in America—Then and Now

- Podcast: Mark Gottlieb on Rabbi Soloveitchik’s “Everlasting Hanukkah”

- Podcast: Ambassador Ron Dermer Looks Back on His Years in Washington

- Podcast: Richard Goldberg on the Future of Israeli-Saudi Relations

- Podcast: Matti Friedman on the Russian Aliyah—30 Years Later

- Podcast: Daniel Gordis on America, Israel, and the Sources of Jewish Resilience

- Podcast: John Podhoretz on 75 Years of Commentary

- Podcast: Michael McConnell on the Free Exercise of Religion

- Podcast: Ruth Wisse on Five Books Every Jew Should Read

- Podcast: Dan Senor on the Start-Up Nation and COVID-19

- Podcast: Reflections for the Days of Awe

- Podcast: Haviv Rettig Gur on Israel’s Deep State

- Podcast: Ruth Wisse & Hillel Halkin on the Authors Who Created Modern Hebrew Literature

- Podcast: Gil Troy on Never Alone

- Podcast: Jared Kushner on His Approach to Middle East Diplomacy

- Podcast: Ambassador Ron Dermer on the Israel-U.A.E. Accord

- Podcast: Micah Goodman on Politics, Power, and Kingship in Deuteronomy

- Podcast: Michael Doran on China‘s Drive for Middle Eastern Supremacy

- Podcast: Peter Berkowitz on Unalienable Rights, the American Tradition, and Foreign Policy

- Podcast: Wilfred McClay on the Historic Jewish-Christian Rapprochement

- Podcast: Amos Yadlin on the Explosions Rocking Iran

- Podcast: Jason Bedrick on School Choice, Religious Liberty, and the Jews

- Podcast: Meir Soloveichik on the Genius of Rabbi Norman Lamm

- Podcast: Tara Isabella Burton on Spirituality in a Godless Age

- Podcast: Gary Saul Morson on “Leninthink“

- Podcast: David Wolpe on The Pandemic and the Future of Liberal Judaism

- Podcast: Chaim Saiman on the “Zoom Seder“ and Its Discontents

- Podcast: Leon Kass on Reading Exodus and the Formation of the People of Israel

- Podcast: Einat Wilf on the West‘s Indulgence of Palestinian Delusions

- Podcast: Matti Friedman—The End of the Israeli Left?

- Podcast: Yehoshua Pfeffer on Haredi Society and the COVID-19 Crisis

- Podcast: Menachem Wecker on Yoga and Idolatry

- Podcast: Moshe Koppel on How Israel‘s Perpetual Election Came to an End

- Podcast: Michael Doran on Coronavirus in Iran

- Podcast: Yossi Klein Halevi on the Transformation of Israeli Music

- Podcast: Richard Goldberg on the Future of Iran Policy

- Podcast: Rafael Medoff on Franklin Roosevelt, Rabbi Stephen Wise, and the Holocaust

- Podcast: Eugene Kontorovich on the Trump Peace Plan

- Podcast: Mark Gottlieb on Jewish Sexual Ethics

- Podcast: Michael Avi Helfand on Religious Freedom, Education, and the Supreme Court

- Podcast: Joshua Berman on Biblical Criticism, Faith, and Integrity

- Podcast: Ruth Wisse on What Saul Bellow Saw

- Podcast: Daniel Cox on Millennials, Religion, and the Family

- Podcast: Yuval Levin on Rebuilding American Institutions

- Podcast: Neil Rogachevsky on Israeli Electoral Reform

- Podcast: Yuval Levin on the Remarkable Legacy of Gertrude Himmelfarb

- Podcast: Best of 2019 at the Tikvah Podcast

- Podcast: Arthur Herman on China and the U.S.-Israel “Special Relationship”

- Podcast: Walter Russell Mead on Israel and American Foreign Policy

- Podcast: Senator Joseph Lieberman on American Jews and the Zionist Dream

- Podcast: Eugene Kontorovich on America and the Settlements

- Podcast: David Makovsky—What Can We Learn from Israel’s Founders?

- Podcast: Christine Rosen on Thinking Religiously about Facebook

- Podcast: Jacob Howland—The Philosopher Who Reads the Talmud

- Podcast: Dru Johnson, Jonathan Silver, & Robert Nicholson on Reviving Hebraic Thought

- Podcast: Thomas Karako on the U.S., Israel, and Missile Defense

- Podcast: David Bashevkin on Sin and Failure in Jewish Thought

- Podcast: Matti Friedman on Israel, the Mizrahi Nation

- Podcast: Micah Goodman on Shrinking the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict

- Podcast: Jack Wertheimer on the New American Judaism – Part III

- Podcast: Meir Soloveichik on the Meaning of Kashrut

- Podcast: Avi Weiss on the AMIA Bombing Cover-Up

- Podcast: Jack Wertheimer on the New American Judaism – Part II

- Podcast: Jack Wertheimer on the New American Judaism – Part I

- Podcast: Jeremy Rabkin on Israel and International Law

- Podcast: Yehoshua Pfeffer on Haredi Politics and Culture

- Podcast: Mona Charen on Sex, Love, and Where Feminism Went Wrong

- Podcast: Dara Horn on Eternal Life

- Podcast: David Evanier on the Rosenbergs, Morton Sobell, and Jewish Communism

- Podcast: Michael Doran on America’s Standoff with Iran

- Podcast: Daniel Krauthammer on His Father’s Jewish Legacy

- Podcast: Yaakov Katz on Shadow Strike

- Podcast: Annika Hernroth-Rothstein on the Miracle of Jewish Continuity

- Podcast: Menachem Wecker on What’s Wrong with the Jewish Museum

- Podcast: Francine Klagsbrun on Golda Meir—Israel’s Lioness

- Podcast: Jonathan Neumann on the Left, the Right, and the Jews

- Podcast: Matti Friedman on Israel’s First Spies

- Podcast: Dovid Margolin on the Rebbe’s Campaign for a Moment of Silence

- Podcast: Scott Shay on Idolatry, Ancient and Modern

- Podcast: Joshua Berman on Whether the Exodus Really Happened

- Podcast: Daniel Gordis on the Rift Between American and Israeli Jews

- Podcast: Nicholas Gallagher on Jewish History and America’s Immigration Crisis

- Podcast: Special Envoy Elan Carr on America’s Fight against Anti-Semitism

- Podcast: Malka Groden on the Jewish Family and America’s Adoption Crisis

- Podcast: Eugene Kontorovich Explains Congress’s Effort to Counter BDS

- Podcast: David Wolpe on the Future of Conservative Judaism

- Podcast: Michael Doran on America’s Allies and America’s Enemies

- Podcast: Jonah Goldberg on Marx’s Jew-Hating Conspiracy Theory

- Podcast: Ambassador Danny Danon Goes on Offense at the U.N.

- Podcast: A New Year at the Tikvah Podcast

- Podcast: The Best of 2018

- Podcast: Jacob J. Schacter on Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik and the State of Israel

- Podcast: Chaim Saiman on the Rabbinic Idea of Law

- Podcast: Daniel Polisar on Herzl’s “The Menorah”

- Podcast: Yehoshua Pfeffer on Haredi Conservatism

- Podcast: Leon Kass on His Life and the Worthy Life

- Podcast: Clifford Librach on the Reform Movement and Jewish Peoplehood

- Podcast: Michael Doran on Theology, Zionism, and American Foreign Policy

- Podcast: Sohrab Ahmari on Sex, Desire, and the Transgender Movement

- Podcast: Yoram Hazony on the Bible’s Political Teaching

- Podcast: John Podhoretz on the Best and Worst of Jewish Cinema

- Podcast: Jamie Kirchick on Europe’s Coming Dark Age

- Special Podcast: Introducing Kikar – Elliott Abrams on Hamas, Gaza, and the Case for Jewish Power

- Podcast: Ruth Wisse on the Nature and Functions of Anti-Semitism

- Podcast: Jeffrey Saks on Shmuel Yosef Agnon

- Podcast: Samuel Goldman on Christian Zionism in America

- Podcast: Martin Kramer on Ben-Gurion, Borders, and the Vote That Made Israel

- Podcast: Russ Roberts on Hayek, Knowledge, and Jewish Tradition

- Podcast: Yossi Klein Halevi on Moving In and Out of Extremism

- Podcast: Charles Freilich on the U.S.-Israel “Special Relationship”

- Podcast: Jeffrey Salkin on ”Judaism Beyond Slogans”

- Podcast: Erica Brown on Educating Jewish Adults

- Podcast: Mark Dubowitz on the Future of the Iran Deal

- Podcast: Greg Weiner on Moynihan, Israel, and the United Nations

- Podcast: Daniel Polisar on Nationhood, Zionism, and the Jews

- Podcast: Jon Levenson on the Danger and Opportunity of Jewish-Christian Dialogue

- Podcast: Leora Batnitzky on the Legacy of Leo Strauss

- Podcast: Wilfred McClay on America’s Civil Religion

- Podcast: Robert Nicholson on Evangelicals, Israel, and the Jews

- Podcast: Charles Small on ”The Changing Face of Anti-Semitism”

- Podcast: Daniel Mark on Judaism and Our Postmodern Age

- Podcast: Ruth Wisse on the Perversity of Brilliance

- Podcast: Daniel Troy on ”The Burial Society”

- Podcast: Matthew Continetti on William F. Buckley, the Conservative Movement, and Anti-Semitism

- Podcast: Jonathan Sacks on Creative Minorities

- Podcast: Elliott Abrams on ”Dictatorships and Double Standards”

- Podcast: Jay Lefkowitz on His Life in the Arena

- Podcast: Michael Doran on America’s Middle East Strategy

- Podcast: Gabriel Scheinmann on Bombing the Syrian Reactor

- Podcast: Elliott Abrams on His Calling and Career

- Podcast: Jeffrey Bloom on Faith and America’s Addiction Crisis

- Podcast: Gil Student on the Journey into Orthodoxy

- Podcast: Meir Soloveichik on ”L’Chaim and Its Limits”

- Podcast: Michael Makovsky on Churchill and the Jews

- Debating Zionism: A Lecture Series with Dr. Micah Goodman

- Podcast: Neil Rogachevsky on the Story Behind Oslo

- Podcast: Mark Gottlieb on Jewish Education

- Podcast: Mitchell Rocklin on Jewish-Christian Relations

- Podcast: Liel Leibovitz on the Jewish Poetry of Leonard Cohen

- Podcast: Ruth Wisse on Tevye the Dairyman

- Podcast: Samuel Goldman on Religion, State, and the Jews

- Podcast: Leon Kass on the Ten Commandments

- Podcast: Ruth Wisse on Cynthia Ozick’s ”Innovation and Redemption”

- Podcast: Yossi Klein Halevi on Ze’ev Jabotinsky’s “The Iron Wall“

- Podcast: Tevi Troy on the Politics of Tu B’Shvat

- Podcast: Jay Lefkowitz & Mitchell Rocklin on the Jewish Vote

- Podcast: Yuval Levin on the Long Way to Liberty

- Podcast: Ruth Wisse on Sartre and Anti-Semitism

- Podcast: Edward Rothstein on Jerusalem Syndrome at the Met

- Podcast: Matthew Continetti on Irving Kristol’s Theological Politics

- Podcast: Meir Soloveichik on King David

- Podcast: R.R. Reno on ”Faith in the Flesh”

- Podcast: Arthur Herman on Why Everybody Loves Israel

- Podcast: Peter Berkowitz on a Liberal Education and Its Betrayal

- Podcast: Meir Soloveichik on Rembrandt, Tolkien, and the Jews

- Podcast: Yoram Hazony on Nationalism and the Future of Western Freedom

- Podcast: Jason Bedrick on Jewish Day Schools and School Choice

- Podcast: Allan Arkush on Ahad Ha’am and “The Jewish State and Jewish Problem”

- Podcast: Bret Stephens on the Legacy of 1967 and the U.S.-Israel Relationship

- Podcast: Jay Lefkowitz on Social Orthodoxy

- Podcast: Norman Podhoretz on Jerusalem and Jewish Particularity

- Podcast: Michael Doran on Western Elites and the Middle East

- Podcast: Ruth Wisse on Campus Anti-Semitism

- Podcast: Meir Soloveichik on ”Confrontation”

- Podcast: Yuval Levin on Religious Liberty

- Podcast: Elliott Abrams on Israel and American Jews